Think Again - Active vs Passive Funds

Can actively managed funds ever win over passively managed funds?

We favor the comfort of conviction over the discomfort of doubt - Adam Grant

Truth be told, I was never a big fan of self-help books. It’s not like I haven’t tried reading any of them. I have read multiple books from the likes of Robin Sharma and James Clear but somehow it never felt interesting.

One exception that I recently found was Think Again written by Adam Grant. It showcases the importance of having the ability to rethink your assumptions and question your convictions.

The book made me question some of the ‘100% conviction’ thoughts I had regarding investing. One of the most common things that you hear while you start investing is to always go with passive index funds. Every Tom, Dick, and Harry just getting started with investing as well as veterans such as Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger swear by index funds.

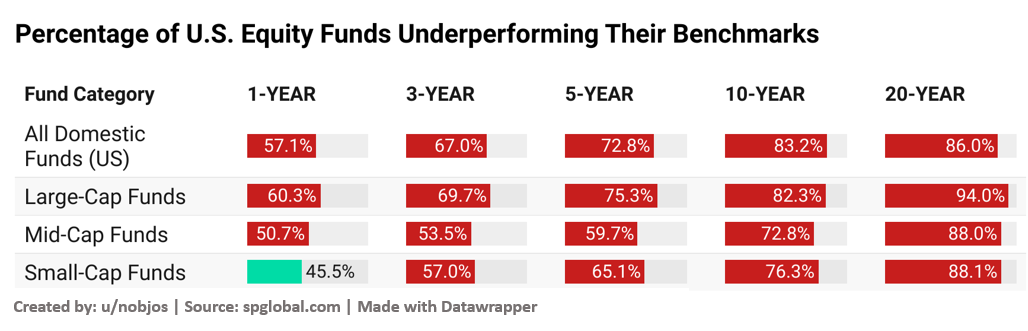

There are countless articles and videos that bash actively managed funds, and you must have definitely heard that “x% of actively managed funds failed to beat the market with x being usually greater than 80%”. I too had done an analysis last August which showcased that very very few actively managed funds beat the index.

But today we will give actively managed funds a slightly unfair chance. Instead of just focusing on all the research that shows why they don’t work, let’s focus on the cases where they work. After all, it’s estimated that there will be $87.6 Trillion globally under active management by 2025 (60% of the total market share) and they should be doing something right to still have the majority market share.

Why do actively managed funds have a bad rap?

Actively managed funds have a simple problem - management fees. It can vary anywhere between 0.5% to 2% when compared to the ~0.1% fee of passively managed funds. While the 1% haircut does not seem high, the impact it makes over the long term is incredible.

For someone who starts investing at 25 and retires at 65, a 1% reduction in expense ratio can increase their savings by $220K giving almost 10 years in extra spending1. So unless the fund can consistently beat the market over a 40-year period (which is very unlikely as we saw from the first chart), the investor is bound to make a lower return than his peer who invested in a passive fund. This is exactly why so many people including me swear by passive funds.

The Outliers

When someone tells me that nobody can beat the market consistently over a long time period, I show them the chart below. The Medallion Fund created by Jim Simons has managed to consistently beat the market for more than 30 years. Since its creation, the fund has only lost money in a single year (1989). For the next 30 continuous years, there was not even a single year where their returns dropped below 20%. Even at the peak of the 2008 financial crisis, the fund had made an 82% gain net of fees2!

And it’s not like Medallion is the only fund that’s doing this out there. Warren Buffet, Peter Lynch, and multiple active Mutual funds have beaten the market consistently over the last 30-40 years (some even after adjusting for the risk).

While these definitely can be classified as the Outliers, there are enough examples of these to show that it’s not just pure luck that drives the returns, and with adequate due diligence and proper management, it’s possible to beat the market consistently over the long run.

But, we shouldn't be trying to pick lone winners - what we should be doing is picking actively managed funds in categories and markets where they have a higher chance of beating the market. So,

When does Active win over Passive?

I am leveraging the excellent research done by Fidelity on this topic. As expected, historical data shows that on average Active funds have trailed their passive counterpart in the US Large-Cap segment. I feel there is a significant bias towards these results in the public psyche as the majority of our attention & funds are diverted toward U.S large-cap stocks.

But, if you look at the Small-Cap and International stocks, we can clearly see that Active funds on average have beaten the benchmark after fees. The main reason for this outperformance is that International and Small-Cap markets are generally considered to be less efficient than U.S Large-Cap stocks. e.g, Amazon stock is covered by more than 50 analysts whereas a small-cap company may be covered by 2 or 3 analysts if lucky. Fund managers can effectively leverage this asymmetry to produce market-beating returns.

Also, it’s unfair to compare the performance of all the funds by bucketing them into one single average value. The chances of you putting money into some no-name fund that’s been running for less than a year is close to zero. Adding to this, since fund fees are clearly disclosed, you can compare the fees across established funds and then pick the ones that are lower.

Funds that were shortlisted by filtering out the top 10% of funds based on Assets under management (AUM) and the bottom quartile in management fees were able to beat the benchmark by 0.18% in the U.S Large-Cap segment. The rationale is that Funds with bigger AUM will have the ability to put more resources into research that can help identify better investment opportunities. By controlling for lower fees, you are bettering your chances of beating the benchmark.

Other places where active managers routinely beat the benchmarks are Emerging Markets (There are higher market inefficiencies when compared to the U.S) and the Bond Markets where the fund managers can effectively select bonds with higher returns while adjusting for risk.

What now!

Surprisingly, it does look like active management has its benefits if you are willing to put in some groundwork to find the right ones. I still don’t feel that a 0.18% better return over the index in Large Cap is worth it after doing all the research and you will be better off sticking to the index. But, both in the case of Emerging Market funds and Small-cap equities, actively managed funds vastly outperformed their respective index.

So, sticking to an Index Fund might not be the best decision in all situations. It does make sense to revisit the international and small-cap allocation in your portfolio to see if it does make sense to get some active fund exposure.

Until next week….

Footnotes

The saving phase simulates a participant with a salary of $45,000 at age 25, linearly increasing to $85,000 by age 65, making yearly contributions of 6% of salary at age 25, increasing by 0.5% per year to a maximum of 10% and with a 50% company matching contribution up to the first 6% of salary. In retirement, $63,750 (75% of final salary) is deducted at the beginning of each year. The blue-shaded area shows ending savings with an after-cost investment return of 9% assumed at age 25, linearly decreasing to 6% at age 80 and remaining constant thereafter. Inflation is assumed to be a constant 3%. The tan-shaded area assumes a 1% greater return each year due to reducing the costs of investment by 1%. All amounts are in present-day dollars.

My incredulity and skepticism during this analysis were perfectly captured by Bradford Cornell in his research paper

During the entire 31-year period, Medallion never had a negative return despite the dot-com crash and the financial crisis. Despite this remarkable performance, the fund’s market beta and factor loadings were all negative, so that Medallion’s performance cannot be interpreted as a premium for risk-bearing.

To date, there is no adequate rational market explanation for this performance.

If you enjoyed this piece, please do us the huge favor of simply liking and sharing it with one other person who you think would enjoy this article! Thank you.