Hey everyone, this is a quick-read article from Market Sentiment. It’s a short and interesting read that will introduce you to a new idea in less than 3 minutes.

SPACs are considered a cheaper and faster way to go public than IPOs, but, SPAC's costs are significantly higher when you dig into it.

How high?

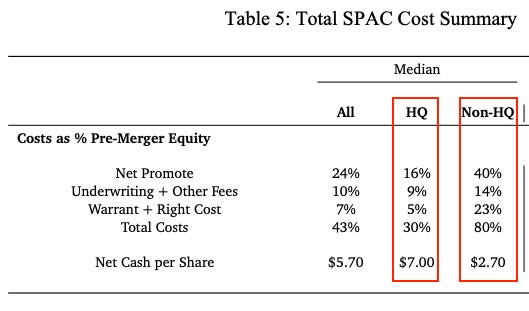

Stanford and New York University researchers1 found that, on average, 58% of pre-merger equity went into servicing the SPAC. i.e., for every $10 raised by a SPAC, only $4.2 is left to contribute to the target company for acquisition. And here's the kicker -- most of these costs are not borne by the companies but by SPAC shareholders who hold shares at the time of the merger.

SPACs also create dysfunctional incentives for the sponsors. Sponsors do very well, even if the SPAC investors do poorly. Even among the SPACs that underperformed Nasdaq by at least 30%, sponsors made, on average, a cool $5 million in profits (187% excess return).

The SPAC structure is simple. It's formed by a sponsor (e.g., Chamath) who engages an underwriter to issue shares to investors in an IPO. SPACs generally raise $10 per share from investors in the IPO and have 2 years to find a target company to merge with (e.g., Virgin Galactic).

If a SPAC cannot find a target within two years, it must liquidate and return all funds to investors with interest. SPACs are usually considered safe as investors have the option to redeem their shares rather than participate in the merger.

While this looks good on paper, most investors overlook the hidden costs and the misaligned incentives between sponsors and investors.

First, the sponsor takes ~20% of the SPAC's post-IPO shares for a nominal price in exchange for establishing and managing the SPAC. Next, the underwriter receives ~5% of the IPO proceeds as fees. (e.g., Credit Suisse made $771 million in revenue in 2021 from SPACs and IPOs). This in combination with accounting, legal, and financial advisory fees can push the overall fee to ~14% of the proceeds.

Finally, on average, the free warrants and rights issued to the IPO investors cost another 14% as this comes at the expense of either the SPAC shareholders who remain invested in the merger or the target company.

Another important metric is the quality of sponsors.

The overall costs incurred are significantly different based on whether the sponsors have an AUM of > $1B or if they have former senior officers of Fortune 500 companies. (Researchers classified them as High quality - HQ)

There's only one way the SPAC and target company shareholders can come out ahead on the deal: If the proposed merger can produce enough value to cover the above costs.

This does not happen for most SPACs.

The target companies know the costs and negotiate a merger agreement where the shares they give up are only worth the net cash, not the $10 per share as investors think. So, the SPAC shareholders who do not redeem bear the costs after the initial hype is over.

The biggest structural flaw of SPACs is that sponsors get rewarded only if they complete a merger. If they merge, they get millions of dollars (even if it's a value-destroying merger); if they don't, they get nothing and lose all their investment.

See the conflict of interest?

Research backs this up. The sponsors do very well even if the SPAC investors do quite poorly. Even among the SPACs that underperformed Nasdaq by at least 30%, sponsors made $5 million in profits (187% excess return), on average.

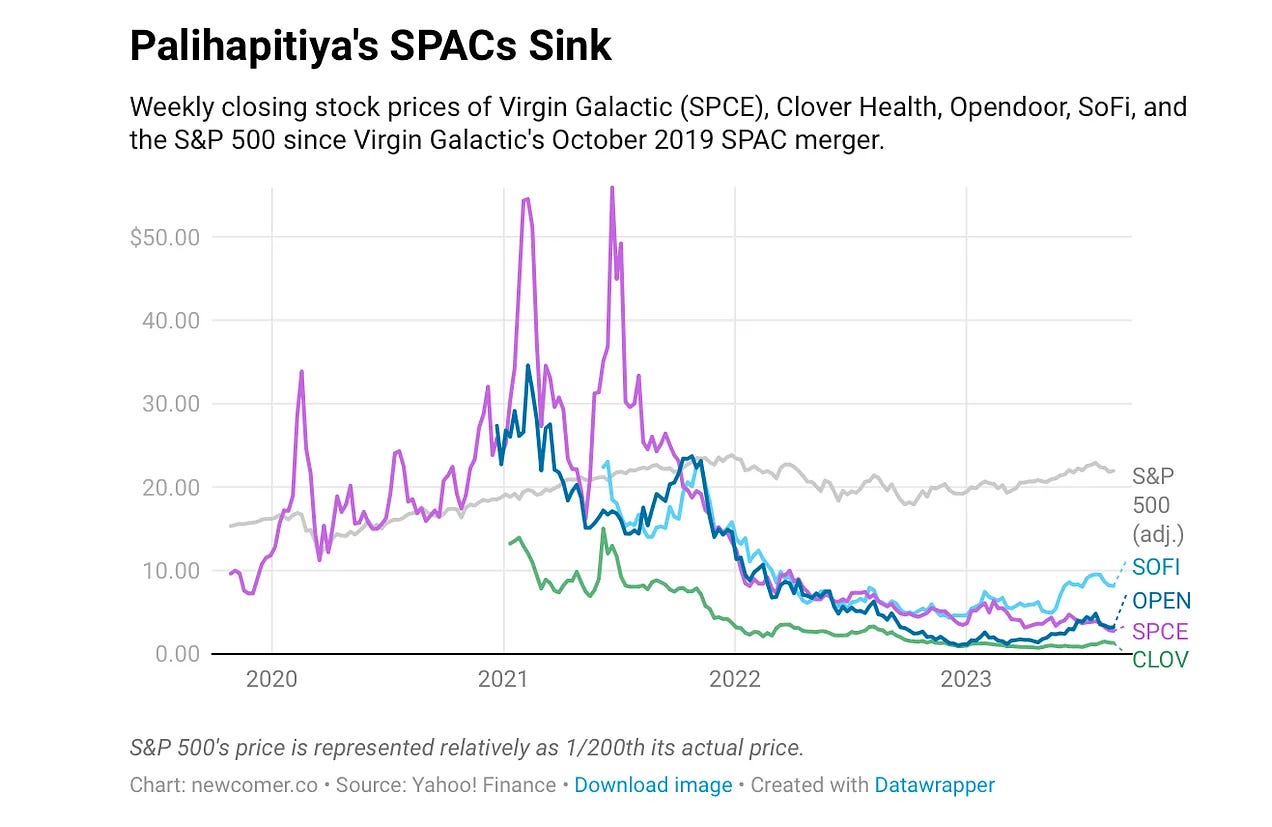

While we don't want to single anyone out, a classic real-life example of this would be “SPAC King” Chamath Palihapitiya. His company made $750 million through SPACs, roughly doubling its money. Compare this to the actual stock performance, and you start to see the issue.

It's not that all SPACs are bad or that sponsors always lead shareholders into bad deals on purpose. The current incentive structure forces their hand into making a deal and the "ex-post experience is consistent with their ex-ante incentives."

Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome. — Charlie Munger

Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. A lot of work goes into these articles and if you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to access all issues. (20% off for annual subscription)

Michael Klausner, Michael Ohlrogge, Emily Ruan — Full paper (open access)