The Buffett Indicator

Understanding and investing using the Buffett Indicator

The Buffett Indicator

The Buffett Indicator is a market valuation metric that compares the total stock market value to GDP. It helps investors assess whether the market is overvalued or undervalued.

The inescapable fact is that the value of an asset, whatever its character, cannot over the long term grow faster than its earnings do. — Warren Buffett

How Interest Rates Drove Stock Market Cycles (‘61–’99)

In his famous speech at the Allen Sun Valley Conference in 1999, Warren Buffett highlighted a peculiar statistic:

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) traded at 874 in 1961 and ended at 875 in 1981. For 17 years, the stock market went nowhere. But, during the same time, both the U.S. GDP and the sales of the Fortune 500 had increased five-fold.

Looking at the next 17 years, from 1982 to 1999, we saw a very different picture. The GDP growth was less than half of the previous period, but the DJIA rose more than ten-fold, from a middling 875 to a stunning 9,181.

The simplest explanation for this mismatch was the change in the Federal Interest Rates. Government bonds went from 4% in 1964 to a dizzying 15% by 1981, dragging down equity prices. In the next 17 years, Paul Volcker successfully brought down inflation and, thereby, the Fed Rate to a reasonable range of 3-5%.

But, buoyed by the stock returns of the last two decades (1980 to 2000), investors were not thinking rationally. In a survey run in 1999, investors who had invested for less than five years expected an annual return of 22.6% over the next ten years. Buffett, on the other hand, with his wealth of experience, expected the stocks to mean-revert, and he predicted that the annual returns for the next 17-year period from 1999 to 2016 would be only ~6%.

I think it's very hard to come up with a persuasive case that equities will over the next 17 years perform anything like they've performed in the past 17.

If I had to pick the most probable return, from appreciation and dividends combined, that investors in aggregate--repeat, aggregate--would earn in a world of constant interest rates, 2% inflation, and those ever hurtful frictional costs, it would be 6%. — Buffett in ‘99

Exactly 17 years later, when Forbes backtested the returns from 1999 to 2016, the annualized total return to investors from the Dow Industrials was 5.9%.

The mismatch between the growth rate of a country and its stock market led Buffett to create the market value of equity (MVE) to the gross domestic product (GDP) ratio. Buffett claimed this to be “probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment”.

MVE/GDP is exceptionally intuitive — The stock prices ultimately reflect a claim of future profits the companies can generate, and GDP measures the total value of goods and services produced in a country. If the former goes up without a proportional rise in the latter, we can reliably assume that fundamentals are not driving the stock price.

What Is Buffett Indicator?

The Buffett Indicator is a simple yet powerful market valuation metric that compares a country's total stock market value to its GDP. The idea is straightforward: if stock prices rise much faster than the underlying economy, something is wrong.

At its core, the indicator reflects whether market enthusiasm is justified by economic growth or if investors are getting ahead of themselves. A high ratio suggests the market is overvalued, while a lower ratio signals the opposite. Though not foolproof, history has shown that when this metric is stretched far beyond historical averages, market corrections aren’t too far behind.

Formula Of Buffett Indicator

A simple way to calculate the ratio is to take the total value of the U.S. stock market and divide it by the annualized GDP.

How to Read the Buffett Indicator?

The Buffett Indicator chart helps visualize stock market valuation in relation to economic growth. Here’s how different levels are typically interpreted:

Buffett Indicator in 2025: How Overvalued is the Market?

As of December 31, 2024, the Total Stock Market Index was $62.7 trillion, while the annualized GDP was approximately $30.3 trillion.

This results in a Buffett Indicator of 207%, which is approximately 67% (or about 2.2 standard deviations) above the historical trend line. This suggests that the stock market is strongly overvalued relative to GDP.

How To Invest Using Buffett Indicator?

Even though Buffett created the indicator two decades ago, there were no significant studies analyzing its forecasting abilities yet. At first glance, the Buffett Indicator does seem to have forecasting abilities, and the best time to invest would be when the indicator is at its lowest.

To test the Buffett Indicator more rigorously, researchers collected data from 14 developed countries going back 50 years. The results from their study give us insights into

Performance of the Buffett Indicator in U.S. and international markets

A simple investing strategy using the Buffett Indicator that gave statistically & economically significant alpha.

Limitations of the Buffett Indicator

Let’s dig in:

Performance of the Buffett Indicator

One classic mistake investors make is using the Buffett Indicator for short-term predictions. Buffett intended the metric to show its power over the long term, and backtests prove the same.

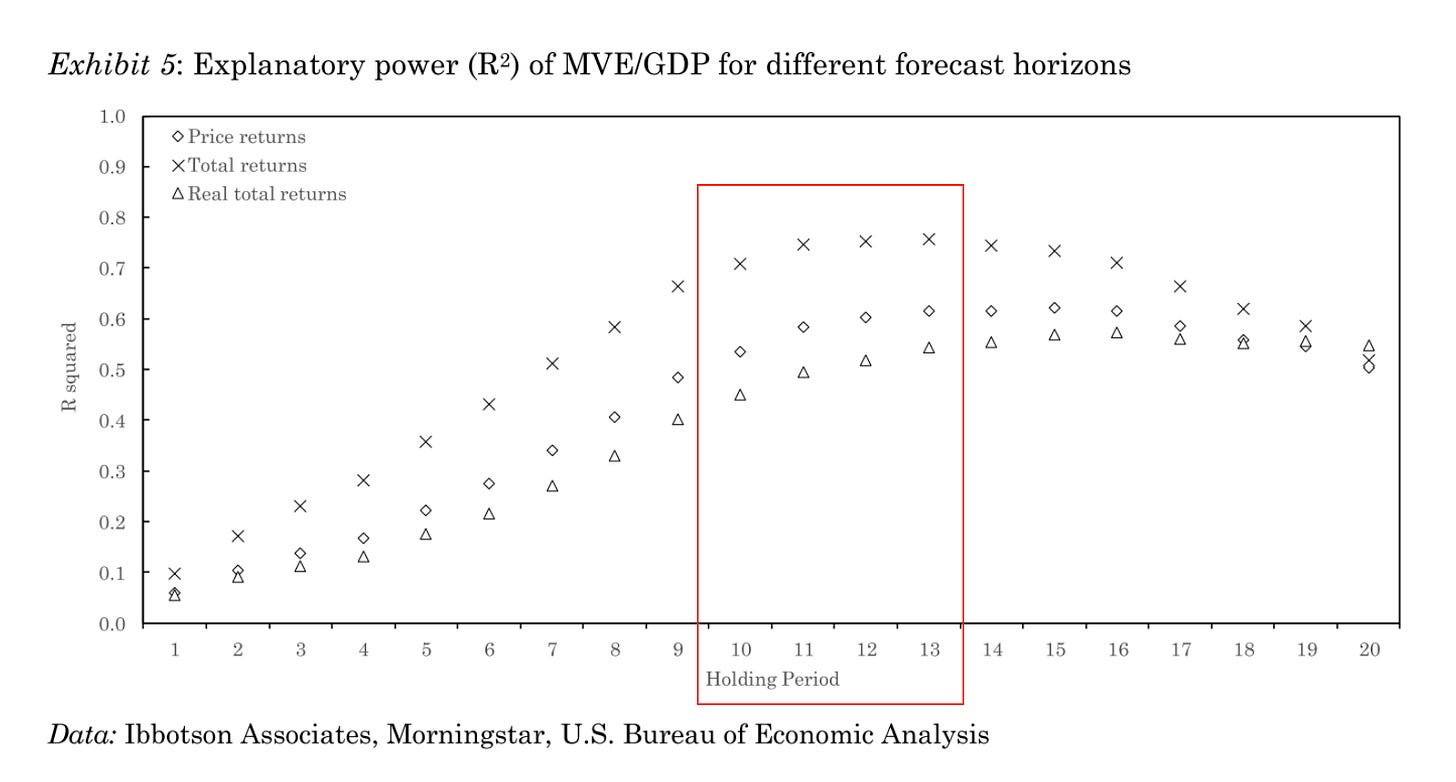

Based on the MVE/GDP data from 1951 to 2019, we see that the predicting power of the Buffett Indicator increases linearly with the holding period (up to 10 years) and then stabilizes.

In the U.S. market, there is a close inverse relationship between the Buffett Indicator and the subsequent 10-year returns. In fact, there was not even a single 10-year period from 1951 to 2019 where the markets had a positive return when the starting MVE/GDP ratio was greater than 130%.

Another group of researchers found similar results in international markets. While there were variations within the countries (more history of financial markets, more explanatory power), the Buffett Indicator explained 83% of the overall return variation of the equal-weighted country data.

Buffett Indicator Strategy for Higher Returns

Given the excellent predictive ability of the Buffett Indicator, it makes intuitive sense to create an investing strategy using it.

The strategy created was simple — They ranked all the 14 countries in the study in an ascending order based on model-predicted returns (using the MVE/GDP ratio) and invested in the top 7 countries based on the predicted returns.

The portfolio was rebalanced once every ten years using the updated MVE/GDP ratio.

Based on the backtest data from 1985 to 2019, this strategy would have

Returned an annualized 10.5% vs. 9.5% of the benchmark

Lower volatility (13.6%) vs. benchmark (14.2%)

Better Sharpe ratio (0.57) vs. benchmark (0.49)

4% reduction in maximum drawdown vs. benchmark

What are the limitations of Buffett's indicator?

While the backtests results are impressive, there are some growing criticisms for timing the market using the Buffett Indicator.

Impact of Interest Rates on the Buffett Indicator

Buffett himself has compared interest rates to the invisible pull of gravity. As the rates change, it affects the value of all financial assets. When the rates are high, investors are more interested in bonds that pay a high return, and consequentially, stocks are less attractive.

After the COVID-19 crisis, when the Fed dropped the rate to zero, investors unsurprisingly piled into stocks. Everyone knew that the market was overvalued based on the Buffett Indicator — But the key question was how long the rates would remain low. While we now know the answer, it was next to impossible to predict accurately in 2021 what the Fed would do.

How Do International Sales Affect the Buffett Indicator?

A key downside of the MVE/GDP ratio is that the numerator (Stock Market Value) reflects the international sales made by the companies, but the GDP does not. As companies become more globalized, more and more revenue will come from international sales (case in point — In the latest quarter, Apple only made 40% of its revenue from the U.S.). This might lead to a rising Buffett Indicator, which does not actually signify that the market is over-valued — Just that American companies are going more global.

The Buffett Indicator historically has shown that market valuations relative to GDP tend to mean revert, and a higher current value points to a lower long-run return.

Given current valuation levels, the likelihood of subdued returns or pronounced market losses over the next ten years is substantial.

MVE/GDP thus corroborates the somewhat sobering return expectations derived from the (raw) Shiller P/E, according to which forward returns will be an order of magnitude smaller than they have been over the past decade. — Swinkels et al. (2022)

While investment decisions should not be based on one metric alone, tempering your expectations about future returns might be the prudent way to optimize your investments.

In the short run, the market is a voting machine. In the long run, it is a weighing machine. Weight counts eventually. But votes count in the short term. And it is a very undemocratic way of voting. Unfortunately, they have no literacy tests in terms of voting qualification, as you have all learned. — Warren Buffett

Buffett Indicator vs. Buffett Index: Is There a Difference?

Many people use the terms Buffett Indicator, Buffett Index, and Warren Buffett Index interchangeably. While the names vary, they all describe the same concept—comparing total stock market value to GDP to determine whether the market is overvalued, fairly valued, or undervalued. The core idea remains unchanged: if stock prices grow significantly faster than the economy, it could signal an overheated market.

FAQ’s

Is the Buffett Indicator accurate?

The Buffett Indicator is a good long-term market guide, but it’s not always accurate in the short term. Factors like interest rates and global company revenues can affect it. It’s best used with other indicators for a full market view.

What is the Buffett Indicator for 2024?

The buffet indicator is a valuation metric that helps investors assess whether the market is overvalued or undervalued. As of December 2024, the US market is at 211% of GDP, 67% above the trend.

How to read the Buffett Indicator?

The Buffett Indicator helps assess whether the stock market is overvalued, fairly valued, or undervalued by comparing the total stock market value to GDP. Below 75% is undervalued,75%-120% is fairly valued, and above 120% is overvalued.

Further reading

The Buffett Indicator: International Evidence — SSRN

The Market Value of Equity-to-Gross Domestic Product Ratio as a Predictor of Long-term Equity Returns: Evidence from the U.S. Market, 1951-2019 — SSRN

The Buffett Indicator — currentmarketvaluation.com

Thank you for reading and being a continued supporter of Market Sentiment. Hit reply to this e-mail to let us know what you think!

Well done