Market Sentiment delivers data-backed, actionable insights for long-term investors. Join 45,000 other investors to make sure you don’t miss our next briefing.

The United States is so powerful that the only country capable of destroying her might be the United States herself, which means that the ultimate terrorist strategy would be to just leave the country alone. — Sebastian Junger, Tribe

Here’s something interesting: What’s common between 1828, 1930, and 2025?

It’s the years in which the United States started mass tariffs.

The last two times did not go so well:

The Tariff of 1828 (aka the "Tariff of Abominations”) was made to protect Northern U.S. industries by taxing imported goods, especially British textiles and manufactured goods. While it benefited Northern manufacturers, it significantly affected the Southern economy, which relied on agricultural exports. It sparked the Nullification Crisis of 1832 and laid the groundwork for the Civil War.

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930): In response to the 1929 stock market crash and rising unemployment, President Herbert Hoover, despite opposition from economists, raised U.S. tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods to record-high levels. Dozens of countries (Canada, France, Britain, etc.) retaliated with their own tariffs, which led to a global trade war. The international trade fell by 60%, and the U.S. farmers, who the act was supposed to protect, lost their export markets. Most economists agree that the act deepened and prolonged the Great Depression.

So what about 2025?

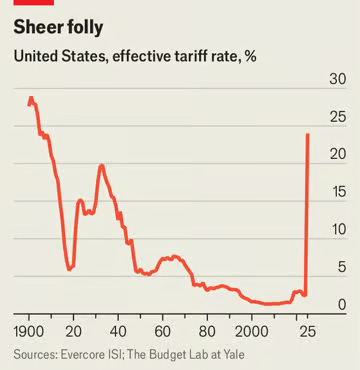

Trump just raised the tariff rates so much that the last time they were this high was in the 1800s! If implemented at this scale, the world economic order and global trade that was painstakingly built after World War II are now dead and buried.

All [mass tariffs] are spaced about 100 years apart because everyone who remembers the last one needs to be dead for the next one to happen. — Stacy

The irony is that, as far as we can tell, this is not a well-thought-out plan.

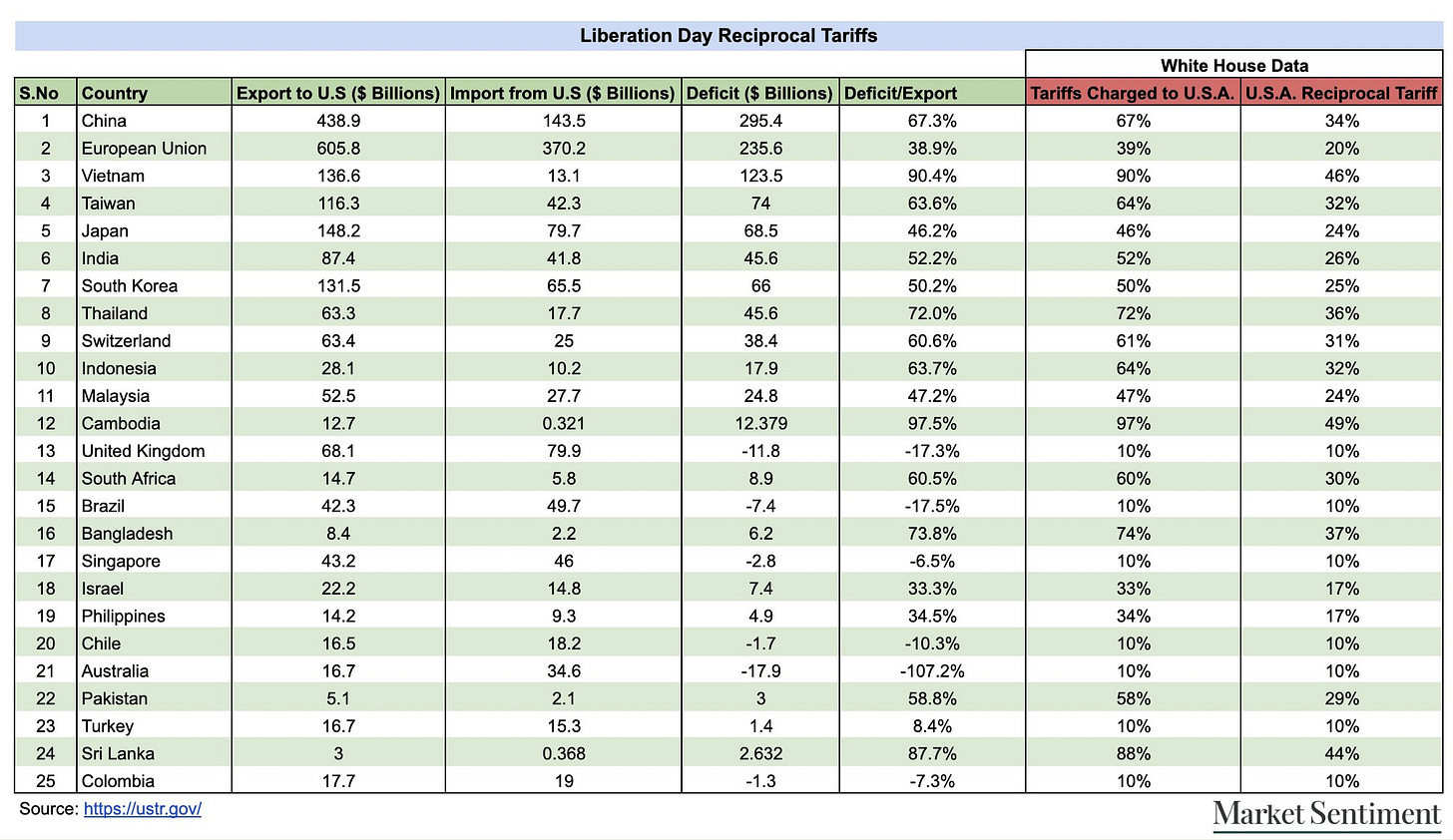

Based on our analysis, the tariffs are calculated by just dividing the trade deficit by exports from that country to the U.S.

For example, consider Taiwan. According to USTR data, the U.S. imported $116 billion worth of goods in 2024 and exported $42.3 billion.

So according to this, Taiwan is charging us a 63.6% tariff and we are going to do a reciprocal tariff of 32% (because giving a 50% discount suddenly makes it fair?)

This makes no sense no matter how you look at it.

U.S. gave Taiwan over $1.5 billion in economic aid after the World War 2 to build out their economic and industrial base. In the 80’s and 90’s, the U.S. helped Taiwan to become the leading manufacturers on semiconductors that U.S. companies take advantage of to this day.

So it's natural that we buy more from them than they buy from us — especially since we helped set up the very industries that benefit us. Add to that the fact that Taiwan has less than one-tenth the population of the U.S., and the average Taiwanese has only one-third the wealth of the average American, they will never be able to buy as much as we can.

Why tariffs don’t work

Here’s a very simple example to highlight of why tariffs are rarely effective:

Mexico makes a hammer for $2. It sells in the USA for $4. If you make the same hammer in the U.S., it will cost $6 so no hammers are made here.

Now U.S. puts 300% tariff on hammer imports so that Mexico hammers now cost $8. The U.S. can now compete and sells its hammers for $8 to make a profit.

But ultimately for the consumer, the hammers now cost $8 instead of $4.

While this might look crude, this is how it more or less plays out every time we have introduced tariffs. Consider what happened in the 1980s.

In the early 1980s, American car companies were struggling against their Japanese counterparts who had cheaper and more fuel efficient cars. In 1981, Ronald Reagan introduced an import quota for Japanese cars that limited the number of cars that can be sold in the U.S.

The quota only ended up hurting the consumers.

[The quota] ended up increasing the cost of cars even though they were manufactured in [the United States]. Overall, all car costs increased, so the consumer lost out. — Susan Stone, economist

President Reagan who introduced the quota soon realized how the tariffs were a mistake.

Sometimes for a short while it works — but only for a short time.

How tariffs will affect the stock market

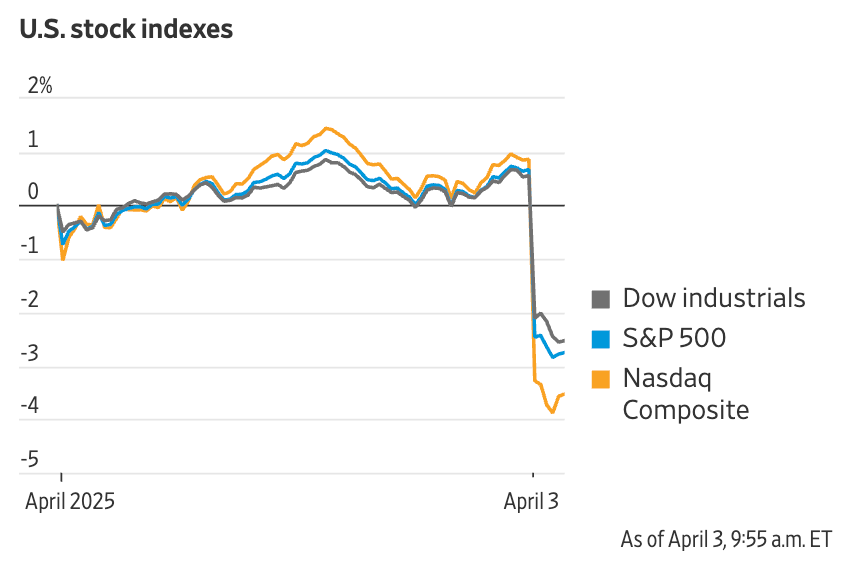

The initial reaction is not great to put it mildly — The stock market is having its worst day of 2025. Approximately $2 trillion has been wiped out from U.S. stocks as the markets face an unprecedented level of uncertainty.

While none of us have a crystal ball, its obvious that certain sectors are going to be impacted more than others.