Sell High

Trading Winners for Losers

“The greatest enemy of a good plan is the dream of a perfect plan. Stick to the good plan.” - John Bogle

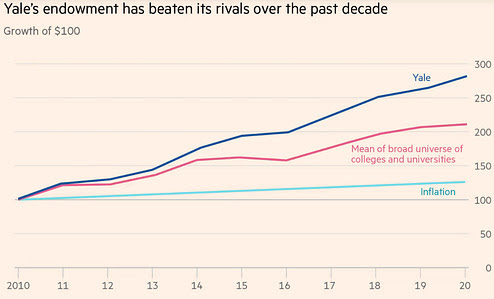

David Swensen was a fascinating figure in the Yale community. At the age of 31, he was tapped to manage Yale’s endowment fund, which, under his guidance grew from $1 Billion in 1985 to nearly $30 Billion in 2019. During his time, he was Yale’s highest-paid employee and credited with the Yale endowment model’s extraordinary performance, which dwarfed pretty much every other Ivy in annualized returns.

His book Unconventional Success lays out strategies for individual investors, which include diversification and index funds as key ingredients. It also emphasizes portfolio rebalancing as a crucial step for hitting your target. But why is rebalancing important?

Picture this: You come across a windfall sum of $100k at the end of 2007. You gauge your risk appetite and invest in a 60-40 equity-bond portfolio. Unfortunately, the next year brings along the great recession, which sees the equities dropping more than 36%, while the bonds go up by 20%. Your portfolio is down ~14% and your asset allocation is out of whack. At the end of 2008, your portfolio allocation consists of 44% in equities and 56% in bonds.

The Prussian general Helmuth von Moltke once said: “No plan survives contact with the enemy”. As the year ends, you face a difficult question: Do you stick to your guns and rebalance your portfolio, bringing it back to the original 60-40 distribution? Doing so would require selling the bonds that held up your portfolio during the crisis and buying equities, which experienced the biggest drawdown in the past 20 years.

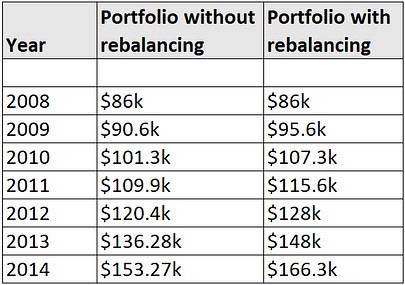

Here is how your portfolio would have fared with and without rebalancing:

Nearly seven years down the line, the non-rebalanced portfolio would be trailing the annually rebalanced portfolio by nearly 8%. Now, a young investor can tide over the difference – but for a retiree with a $1 million portfolio, that's a difference of ~$130k in just 7 years: more than 2.5 times the median annual US retiree income!

We’ve expounded on the merits of holding on to assets (particularly equities) that have experienced drawdowns earlier. However, rebalancing presents a whole other psychological barrier. It requires you to sell your outperforming assets to buy the underperforming ones. What necessitates such an action?

Staying the Course

Sharp market declines may make rebalancing appear a frustrating “way to lose even more money.” But in the long run, investors who rebalance their portfolios in a disciplined way are well rewarded.” – Burton G. Malkiel

Portfolio rebalancing is crucial for managing risk. When investors opt for a 60-40 portfolio instead of an all-equity one, they are intentionally limiting returns to achieve a more controlled level of risk. Portfolios that are not rebalanced experience allocation drift that alter this risk-return balance.

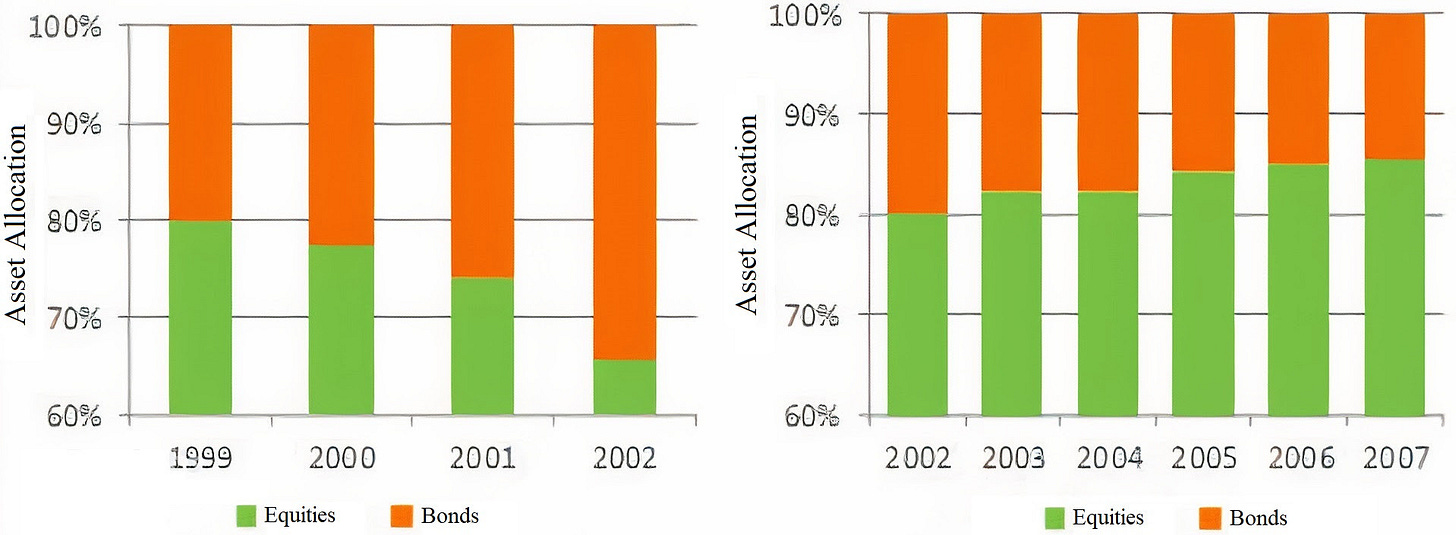

Let us consider two examples: In the first case, an 80/20 (80% stocks and 20% bonds) portfolio in 1999 would have changed to a 65/35 allocation in 2002 following the dot-com bubble. In the second case, an 80/20 portfolio in 2002 would drift to an 85-15 allocation by 2007 due to equity market performance in the lead-up to 2008.

In the first case, allocation drift till 2002 will result in a reduction of portfolio returns from 7.4% to 6.9% (between 2002 to 2022). On a $100k starting portfolio, that is a difference of nearly $37k at the end of 20 years. In the second case, the portfolio drawdown in 2008 will increase from -25% to -28%.

Not rebalancing your portfolio is similar to gradually switching from blackjack to slots in the casino. Even though slot machines offer bigger rewards, you initially chose blackjack because it’s less risky. The driving force behind rebalancing is regression to the mean: over a long period of time, the performance of various assets tends to revert to their historic averages.

Rebalancing also helps in avoiding the hot-hand fallacy. For instance, high-performing equities yielded an average 10% return from 2004 to 2006 and it might have been hard to sell equities at a time like this in favor of acquiring bonds. But just a year later, the Global Financial Crisis prompted a rush to bonds resulting in annualized bond returns of up to 15% – and without selling in the prior year, investors would have missed out on this.

In such cases, automatic rebalancing helps in overcoming the psychological barrier associated with selling high-performing assets. Is there an optimal way to do it?