Risk

Risk is what you don't know you don't know

Risk is an arbitrary concept until you experience it.

Most people only came to know about SpaceX once they achieved their first landing of their Orbital booster in 2015. What most people don’t know is that Musk started the company in 2002 with his proceeds from the sale of PayPal with no other backing.

The company struggled for the first 7 years with a string of failures and was near bankruptcy. (emphasis by author)

I messed up the first three launches. The first three launches failed.

And fortunately, the fourth launch, which was, that was the last money that we had for Falcon 1. That fourth launch worked. Or it would have been — that would have been it for SpaceX. But fate liked us that day. So, the fourth launch worked — Elon Musk in 2017

The company is now wildly successful and is the most valued private company in the U.S. with a $150 billion valuation. It routinely enables cargo and even passenger missions to the International Space Station.

Now, consider the fact that one of the Falcon launches failed due to a busted nut that eventually caused a fuel leak during the launch. While it was initially thought to be a human error, the US defense review concluded that

a small aluminum nut designed to hold the fuel pipe fitting inplace failed due to subsurface corrosion not visible to the naked eye.

All that stood between bankruptcy and an eventual $150 billion company was yet another busted nut or a screw a technician forgot to tighten. Think about all the early investors and employees in the company — we don’t think that they would have ever thought all that stood between a total loss and a 1,000x return on their investment would be a loose nut.

While it worked out for them in this particular case, there were hundreds of investments where it didn’t. This is why identifying and evaluating risk is one of the most important things in investing.

How we view risk:

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman popularized the concept of What you see is all there is in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. It’s a cognitive phenomenon where our brains are wired to believe that the information we have is all the relevant information there is.

The lesser the overlap between the grey and red circles, the riskier the investment. One way to minimize this is to learn more and put more thought and due diligence into our investments. Intuitively, we understand this and expect a higher return when the range of possibilities is higher.

Consider the example of investing in treasury notes vs. an upcoming small-cap. With treasury notes, you are assured a return of 3 to 4% at the end of the year. There is only one highly unlikely scenario of a U.S. default where you would not end up getting the payout.

Compare this to the small-cap where the range of outcomes is much higher. The company can go out of business where you have to mark your investment as a total loss or the company can double its stock price in a year giving you a windfall.

To compensate for this extra uncertainty, you expect a higher return (when compared to the treasury notes). No one would invest in small-caps if their average expected return were comparable to the treasury bonds.

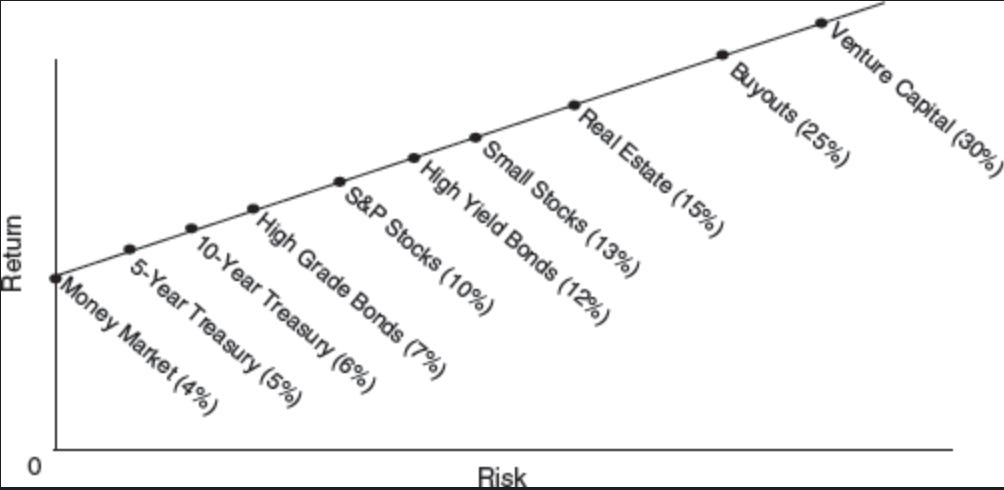

If we extrapolate this logic to all other investments, we get a familiar chart like this:

How we *should* view risk:

The problem with the above approach is that investors make the wrong conclusion after seeing it. It only communicates the positive relationship between risk and return. In good times, it’s easy to look at the high returns of the riskier investments and then think that they should have invested there.

The correct way to think about it would be that in order to attract capital, riskier investments have to offer the prospect of a higher return — Not a guarantee of a higher return. If we add this nuance to the above risk-return chart, we get a much better way to visualize the risk-return relationship.

We see this trend every year in the stock market. Even though the stock market generates 10% annual returns on average, it rarely delivers that in any given year. If you go into the market expecting a 10% return, you will be disappointed.

Now let’s dig into a good framework for quantifying and managing risk: