Hello! I’m putting together this series to bring you diverse experiences and perspectives of other investing writers. This week’s guest is Nick Maggiulli, the writer of the excellent Dollars and Data, and Chief Operating Officer at Ritholtz Wealth Management LLC1.

If you’re new here, you can subscribe by tapping this button for content that will make you a smarter investor.

Of Dollars and Data is a great example of how you can always go deeper into financial topics with a consistent vision without caving to the pressure of novelty. Nick Maggiulli writes about how even God can’t beat Dollar Cost Averaging, Portfolio allocation, how investors should think about money, what risk isn’t, and his trademark idea to “Just Keep Buying” in great detail and from different angles.

Nick has built a voice with his writing that people trust and look to, not only to understand what is going on in the market but also to think and rethink their own relationship with money. One of the reasons is that his articles are based on solid data and historical research, and he does not make claims that he can’t back up. But the more important aspect is the human connection because of his personal stories that illustrate how his thinking about money has changed with time.

Let’s dive into the interview to unpack his approach toward money. In this issue, we cover:

Why you should optimize your income over investments at the beginning.

Why people try to beat the market with statistically impossible strategies.

When and how to select a financial advisor.

How to filter out noise and fake news related to investing.

Which is more important: Asset allocation or asset selection?

Why maxing out your 401k is over-rated – and what the most under-rated investing advice is.

Let’s get started.

Personal Journey

MS: Can you tell me a bit about your personal journey in life and investing? How have your thoughts about money and investing changed over the years?

Growing up, my parents didn’t have much money. Though I never went hungry, I also knew that there was much to go around. As a result of this, my early mindset around money was one of scarcity. Even through college I only ordered off the dollar menu at a fast food restaurant, though I could afford pricier items.

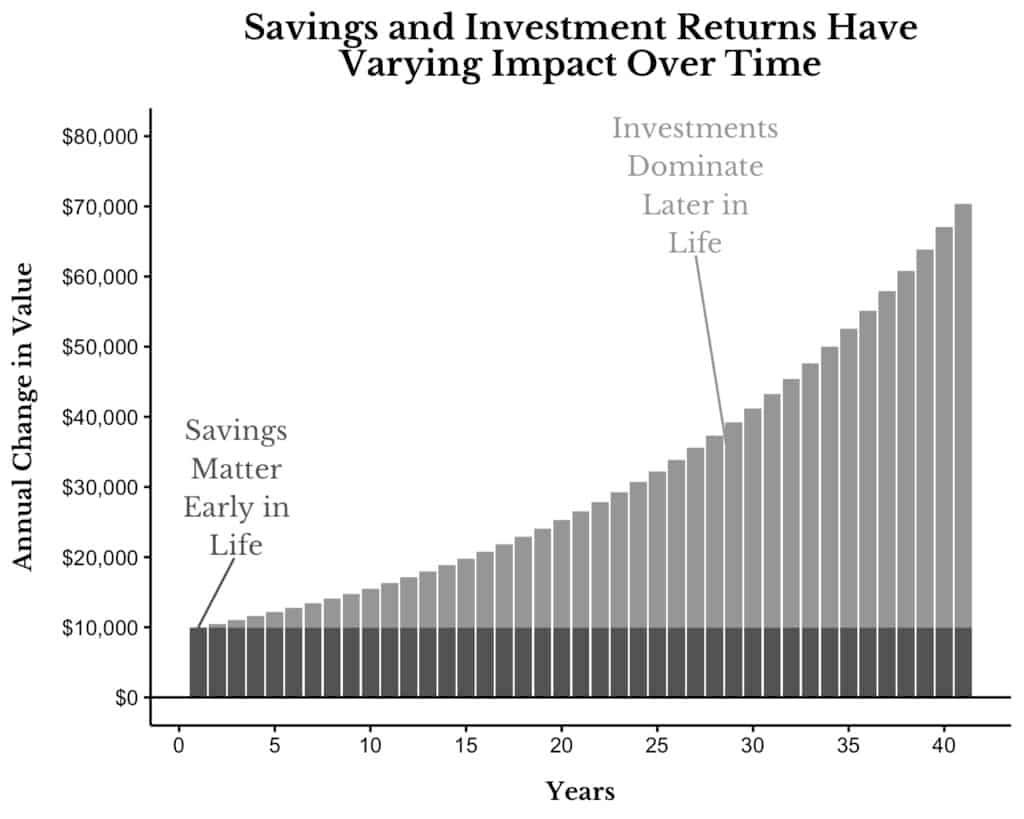

Over time though, this changed. I learned more about personal finance and investing in college and in the years after. As a result, I began to see money as a tool we could use to change our lives. Today I think investing is incredibly important, but its importance becomes more amplified as you have more money (typically later in life). For most people, their career and their income will be the dominant factor in their early financial success, so I try to get people to focus on that more instead of worrying too much about their investments.

MS: Unlike the usual brand of financial content which is very anecdotal, you have a focus on historical analysis and using data to back up your arguments. You have developed your own niche as a result. What motivated you to start writing about investing and how was your approach shaped?

I’ve always had a passion for investing and I also enjoy programming/data science. I saw a potential fit between the two and thought it would be fun to start writing about finance and economics for fun. I eventually found my niche in the investment space and haven’t looked back.

My approach was shaped by questioning a lot of what we hear (which usually isn’t backed by data). So I simply ask: Is that true? Then go about trying to find out. Many times this leads to nowhere, but once in a while I find a surprising conclusion.

(MS: One great example of testing assumptions to find the truth – Should you invest in stocks lump-sum or DCA? What about other assets like Bitcoin? This article covers it all.)

MS: Who are some financial writers who have had an influence on your style?

Early on it was William Bernstein and Jason Zweig, but over the years I’ve become far more influenced by Morgan Housel. Bernstein taught me the importance of analytics and Zweig the importance of human psychology, but Housel taught me the importance of storytelling. As much as analytics matter, we are still humans at the end of the day. And humans are captivated by stories. So if you want your message to spread into the world, you need a good story.

Investor psychology

MS: Your book “Just Keep Buying” is a comprehensive take on all aspects of investing – From the basics of investing to retirement and tax planning. There are some consistent themes in both your book and your blog posts.

For example, you are a staunch advocate of investing in low-cost index funds for most individual investors, and you have written multiple articles about why timing the market and picking stocks are statistically impossible strategies. Why do investors still resort to these strategies? Is it greed? Is it a hope that “this time is different?”? Or do they assume that any chance however small is probably reserved for them?

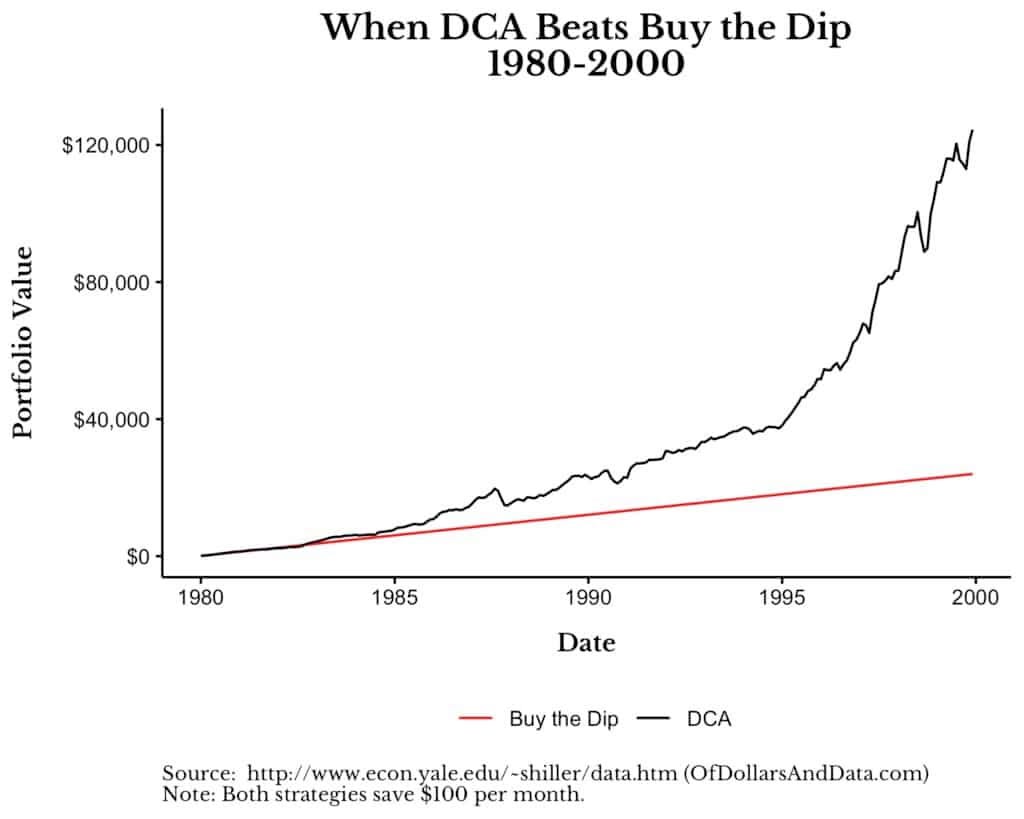

I think the reason most people try to time the market is based on both fear and greed. Selling at the first sign of trouble is fear-based, while “buying the dip” is greed-based. There is no evidence that either strategy works consistently, but they do work at times. I think this distinction is important, because this is why people market time.

If I told you that no one could ever successfully call a top or bottom, I’d be lying. People have done this before and they will do it again. However, I don't think anyone can do this on a consistent basis. That’s where market timers fail. They may be right now, but they will be wrong later.

And in being wrong they could end up missing out on a lot. My favorite example of this was all the people who sold in March 2020 only to see the market hit new all-time highs in less than 6 months. Predicting the future is hard, which is why I don’t try to do it.

MS: I like the book’s emphasis on how fulfillment, not money, should be the thing to optimize for. Why is it so hard to make this switch for people on both ends of the spectrum (net savers and net spenders)? How can they design a place for investing in their life to optimize for fulfillment rather than investment returns?

I think people have to spend a lot of time analyzing their big decisions in life to figure out what is really motivating them. Once you know that, then you can ask yourself whether it makes sense to continue those behaviors.

For example, we always hear the cliche example of the successful person who works so much that they miss their children growing up. It starts with them skipping out on a sports game or a dance recital and never stops after that. My question is: why is that person working so much? The obvious answer is money, but given how successful they are, money probably isn’t the actual reason, it’s something else.

I think by digging deep inside yourself, you can go through the same exercise. Ask yourself why you do the things you do. Why do you work in the job you work? Why this field? Why did you choose this life partner? Etc. The goal is to know yourself and then solve life from there. That’s how you maximize fulfillment.

(MS: Check out Nick’s piece on Why you shouldn’t optimize your life.)

MS: The book provides many rules of thumb and heuristics that can be used right away, like the 2x rule. One trick I found very useful was how restricting choices artificially can actually result in more peace of mind:

“Holding US stocks for three decades is much harder emotionally than paying off a mortgage. When you have a home, you don’t get the price quoted to you daily, and you probably won’t ever see its value cut in half.”

– Nick Maggiulli

Environment design is seldom discussed when it comes to investing. How can investors design their environment to reduce stress in investing?

The best environmental design I know of is partial ignorance—don’t care too much. For example, though I write about money all the time, I rarely think about it in my personal life. I understand that this is a privileged thing to say, but I’m not even a millionaire. I’m just someone who is trying to enjoy life and helping people with their money along the way.

Investment advisors, asset allocation, and risk

MS: Your first article was about how hedge funds get rich where you discussed the role of fees, and how funds seldom beat the market. In such a world, what is the role of investment advisors and money managers? What should investors look for?

When it comes to hiring a wealth manager, you should focus on their approach to financial planning, how they make you feel, and their competence. These are all things that the wealth manager has full control of and things that you can easily analyze. No one can control what the market does, so find someone that adds value beyond the portfolio.

(MS: Read more at “When should you hire a financial advisor?”)

MS: Is asset allocation more important than asset selection? Why?

David Swensen, the late famed investment manager, once said that your portfolio returns come down to three things: asset allocation, market timing, and security selection. And, after reviewing the data, asset allocation represents about 90% of the variability in returns.

So, to answer your question, asset allocation is far more important than asset selection for the vast majority of people. Deciding what risk assets to own and in what proportions will have a bigger impact on your portfolio than just about anything else. Of course, this isn’t an easy task, which is why I tell people to focus on broad diversification no matter what they do.

MS: What are your thoughts on a barbell approach to investing?

I see why people like this approach, but I don’t favor it for behavioral reasons. The barbell approach has you holding lots of low-risk assets (i.e. cash) and lots of high-risk assets (i.e. crypto, single stocks, etc.) at the same time. Unfortunately, I think this approach leads to a higher probability of bad investor behavior when times get tough. I think 2022 is a great example of this where many high-risk assets are down 50% or more, while the overall market is only down 20%.

It’s not that the barbell approach couldn’t work, but I think many people would have a hard time sticking to it over long periods of time. Their higher chance of bailing when times get tough makes it a harder strategy to follow than my “Just Keep Buying” indexing approach.

MS: You have written about the existential risk in stock picking – That you can never know for sure whether you have mastered the skill or whether luck worked in your favor. Why is that important? Someone who thinks they can follow in the footsteps of their investing heroes (like Buffett or Lynch or (gulp) Sam Bankman-Fried) might think that they need to get it right only once. Is that a reasonable way to think about risk?

You don’t need to be right only once to be a great stock picker. You need to be right 6 out 10 times and you have to do that consistently over many decades to be the next Buffett, Lynch, etc.

But do you really need that level of returns to be financially successful? I don’t think so. Most people need far less to live an amazing life. Unless you are trying to be remembered as the next Buffett, there’s no point in trying to be like him (or anyone else).

Once again I would analyze the motivations behind why you want to be a stock picker and determine whether those motivations make sense.

Financial media and perception

MS: How do you think financial media and the abundance of investing resources have affected investor psychology? You have written about how anecdotal stories are sensationalized to grab eyeballs – Can you suggest a simple framework for investors to filter through the noise and assess the validity of financial news and stories in social media?

Ask yourself: is this going to matter 20 years from now? If the answer is no, then maybe you shouldn’t be paying attention to it. This is why I almost never follow macro and don’t think most people should either. It’s mostly wasted time and energy.

MS: The market has always been influenced by perception, but it looks like the last 2-3 years were dominated by perception-based assets. You have written several articles about crypto, the memestock phenomena, etc. as they were happening. Why are narrative-driven assets so hot all of a sudden, and will they become a mainstay?

There are basically two ways in which assets increase in value: fundamentals (increased earnings, value, etc.) and flows (people are bidding them up). You can make money following flows, but it is a difficult game to play especially over long periods of time.

It’s difficult to say which assets will become mainstays based on flows because preferences change over time. What’s hot now may fall out of favor and vice versa. It’s kind of like fashion or music popularity, it varies based on lots of things.

This is why I recommend investing most of your portfolio in income-producing assets. These assets should follow fundamentals in the long run so you can worry less about flows.

MS: A couple of questions from a devil’s advocate POV. Aren’t equities perception-based assets themselves?

Once a stock is out in the market, what tethers it to a company’s performance? Is it just the regulatory framework and institutional infrastructure?

Does that mean regulation can make crypto mainstream like equities?

Well, technically, every asset is based on what other people are willing to pay for it. So while this can vary from fundamentals (i.e earnings and earnings growth) in the short run, it should converge in the long run.

Regulation might make crypto more mainstream, but there will also need to be other use cases for it other than speculation.

MS: A lot of the debate around crypto has been the idea behind the asset. But are exchanges and the infrastructure the bottleneck that nobody is thinking about?

FTX and several other exchanges were not crypto themselves, they were the gateway to access the crypto world, and that was the weak link. When we do a historical analysis of equity markets, are we over-rating the robustness of the equity market infrastructure? They are only a few hundred years old after all.

Equity infrastructure had at least a few hundred years to evolve, which is a feature, not a bug. Crypto tried to go mainstream in 10 years without any such process and we are seeing the results of that today.

I find it ironic that the group of people who support a system based on not trusting others ended up putting so much trust into so few individuals. I never hold my crypto on an exchange and you shouldn’t either.

Personal experience and working with data

MS: Your article on viaticals blew my mind – arbitraging death to make money is the most metal idea in finance I’ve come across. Are there any other such wild strategies that people don’t know about?

There definitely are but access tends to be limited (based on bankroll). I also wouldn’t recommend any of these approaches for most retail investors as they may require more expertise. This could include things like litigation finance (financing lawsuits) and royalty investing.

MS: Your articles on your personal experiences and how they influenced your thinking about money and life are some of my favorites - For example, Regrets, It’s never too late to change, and Losing more than a bet.

Personal experience has a huge impact on how people think about money. Sometimes it can have the opposite effect, where people generalize unique cases they know about (like a successful entrepreneur or a lottery winner, without taking survivorship bias into account) and apply it to themselves. What’s a healthy way to incorporate personal experiences into the way you think about money and life, by placing them in the appropriate context?

Great question. I think the best way to incorporate personal experience without getting biased is to also consider what the data shows. I don’t think data is a silver bullet, but if your experience doesn’t fit the typical outcome then you might want to adjust your beliefs accordingly. Of course, there will always be exceptions to this, so use your judgment accordingly.

(MS: Check out Nick’s article on Why Personal Finance has become a bit too personal)

MS: Apart from backing your articles with historical data, you also open-source your analysis programs written in R and share the links. If someone wants to adopt a data-driven approach to testing their own ideas and assumptions as an individual investor, where can people start? Do you have any suggestions about the road to becoming a data-driven investor?

I think everyone should start where they are comfortable and work from there. If that means Excel, that’s fine. I suggest learning how to do financial math (I.e. How to move money through time, How to calculate drawdowns, etc.). There’s lots of value in understanding the basics very well because you can always fall back on them.

Closing thoughts

MS: What is one idea you discovered in the last few years that blew your mind and changed the way you think about something?

The book Die with Zero. Many of us are over-saving and we probably don’t realize it. Better to spend more of your money while you can then die the richest person in the graveyard. It completely changed how I viewed spending money and I would recommend it to anyone.

MS: What is the most over-rated idea in investing?

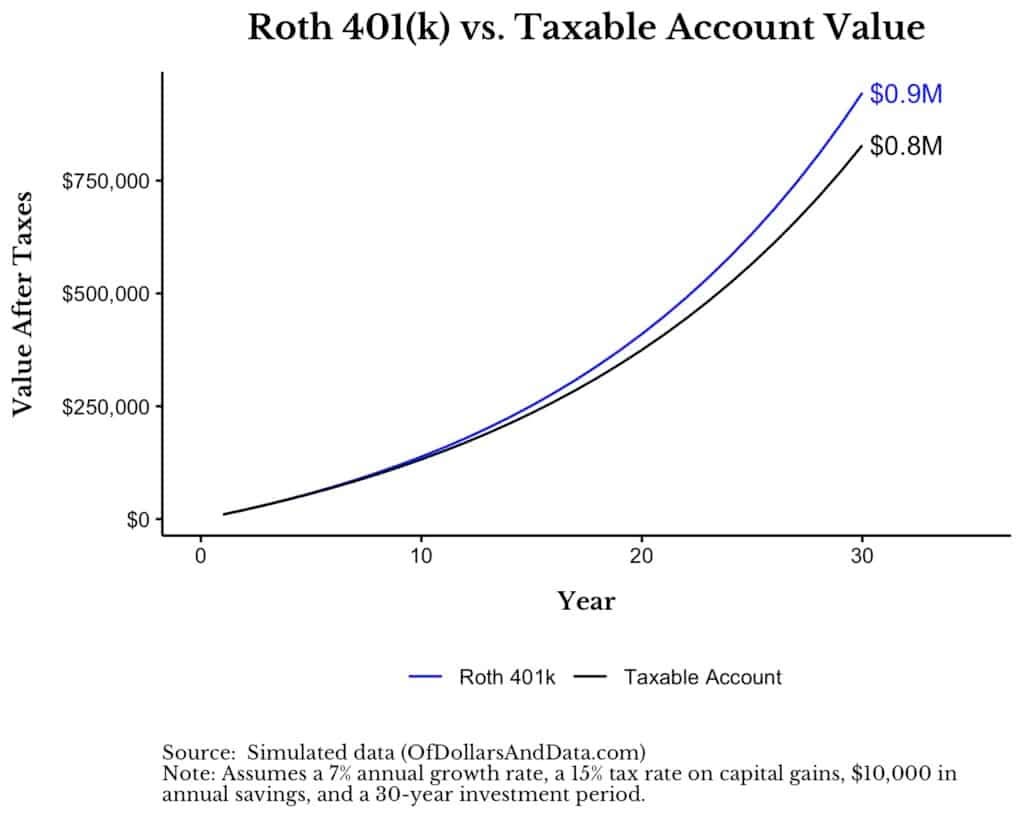

For those in the U.S., it’s maxing out their 401(k). Think there is far more to life than saving money in retirement and think the tax benefits aren’t as large as many believe. Of course I support saving for retirement, but I think there are probably too many people maxing that don’t need to be. (MS: Check out Nick’s article on Why you shouldn’t max out your 401k for a detailed explanation)

MS: What is the most underrated idea in investing?

Return on hassle. The basic idea is that higher returns aren’t always better if you have to spend more time/energy to get them. For example, there are a lot of real estate investors who have “passive” income that isn’t quite so passive. Dollars and cents matter, but HOW you earn those dollars and cents matter too.

MS: Is there a book, podcast, a blog, or anything else - that you would like to leave as a recommendation to readers?

Check out Money With Katie and Jack Raines. My two favorite relatively newer bloggers in the finance world.

MS: Do you have any idea or suggestion that our readers can take away to become more well-informed investors, or even make investing a little more enjoyable and stress-free?

I’d assume most of the people reading this are doing relatively well financially. Therefore, I think their problem won’t be growing their wealth over time, but how to spend their wealth to live a fulfilling life. This isn’t as easy as it sounds. You have to work at it actively.

So I’d recommend spending time on that. Be purposeful. Figure out what you really want. Life becomes much easier after that. Thank you for reading.

Thank you so much for reading and being a continued supporter of Market Sentiment! If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and tell a friend about us. You can even forward this paywalled content to a few friends for free :)

But first head over to Of Dollars and Data to read more of Nick’s writing, and check out his book “Just Keep Buying” on Amazon. It’s a great book to think about investing holistically, whether you are a beginner or a seasoned investor.

Were there any topics you wanted to know more about? Whom do you want me to interview next? Let me know in the comments!

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Please do your own research before investing.

All views are Nick Maggiulli’s alone and do not reflect the opinions of Ritholtz Wealth Management LLC and its affiliates.