We are publishing this without a paywall. Please share widely.

Nassim Taleb, in his 2012 book Antifragile, expanded on an interesting idea known as the Lindy Effect — If something has been around for a long time, then the probability that it will stick around for longer is higher.

This partially explains why people still read Shakespeare and Socrates but forget the bestsellers from the last decade.

If a book has been in print for forty years, I can expect it to be in print for another forty years. But, and that is the main difference, if it survives another decade, then it will be expected to be in print another fifty years.

"This, simply, as a rule, tells you why things that have been around for a long time are not “aging” like persons, but “aging” in reverse. Every year that passes without extinction doubles the additional life expectancy. This is an indicator of some robustness. The robustness of an item is proportional to its life!

For the perishable, every additional day in its life translates into a shorter additional life expectancy. For the nonperishable, every additional day may imply a longer life expectancy. — Nassim Taleb

Half of all companies fail within five years, and 80% in the first 20 years. However, some companies become outliers and survive for hundreds of years. So, in theory, the Lindy Effect applies to companies.

Take Coca-Cola, for example — The company was founded in 1892 and survived the Great Depression, two World Wars, and the 1980s Cola wars, just to name a few. Not only did the company survive all this, it has thrived and increased its dividends for the past 61 consecutive years. Based on the Lindy Effect, Coca-Cola has a better chance of making it to the next century than Google.

If you are a value investor, this is an important but often overlooked factor. Ultimately, the company valuation is based on the present value of future cash flow. The problem with the current valuation technique is that we always project that the company will survive in perpetuity.

This is why it becomes so hard to value companies in their growth stage. A classic example is that during the dot-com bubble, economist Burton Malkiel pointed out that at Cisco’s implied growth rate (Cisco was only 15 years old at that time), it would become larger than the entire U.S. economy within 20 years.

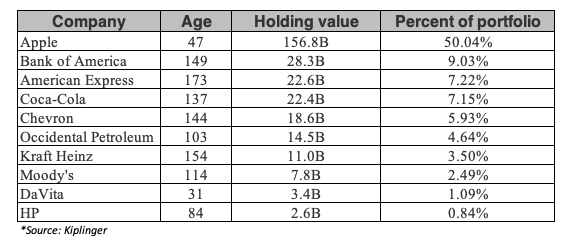

But, once a company has matured, it will have an established brand, a loyal customer base, and a strong market position, making it easier to assign a fair value to the company. Buffett understands this intuitively, and it’s one of the key reasons why he only invests in established companies — The average age of the top 10 holdings of Berkshire is 113 years, with seven companies older than 100 years!

Performance of Lindy stocks

Survival is only half the story.

What we are really curious about is how legacy companies have performed over the long run. On one hand, older firms will have better structure, more efficient processes, better levels of productivity, and an easier time attracting new talent. But, on the downside, older firms will have a negative base effect (they tend to be larger), lower sales growth, and tend to move slowly.

To test this, we are leveraging this excellent dataset created by Boris Marhanovic, where he consolidated all public companies in the U.S. that were more than 100 years old. There were 485 companies on the list, and after some data cleaning, we are left with 73 target companies that we can consider as Lindy stocks.

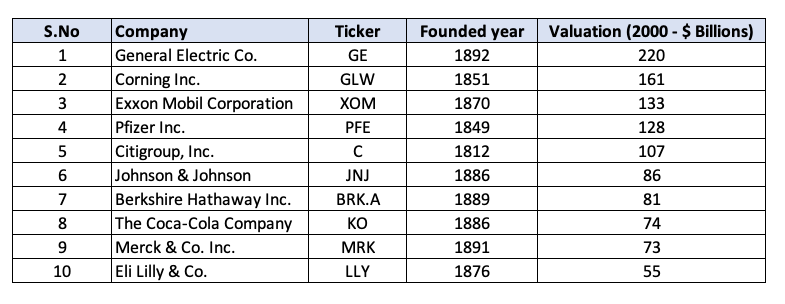

To give you a flavor of the type of companies that we are investing in, below are the top 10 companies from our list of Lindy stocks.

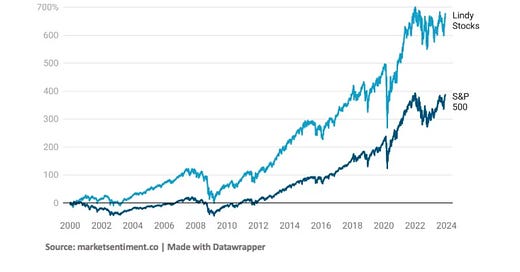

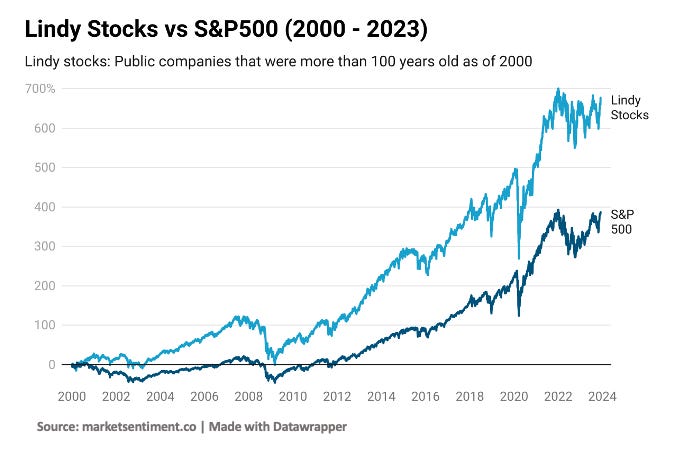

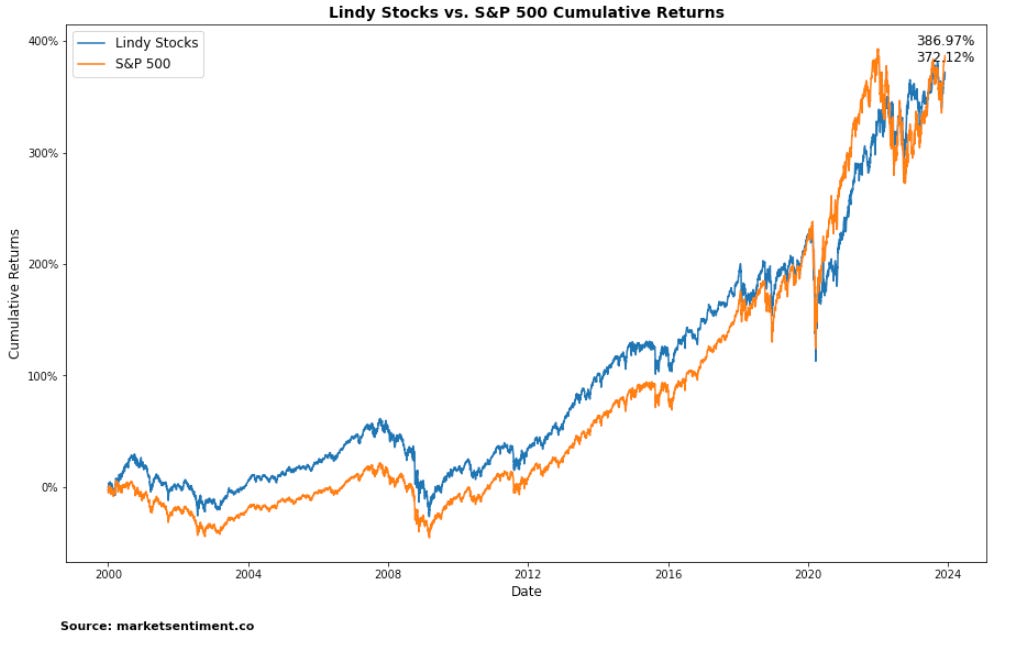

The results are surprisingly in favor of the Lindy stocks. $100 invested in Lindy stocks would have grown into $776 (676% return) compared to only $486 (386% return) if you had invested in the S&P 500. The cherry on top was that this outperformance was achieved with comparable portfolio volatility (12.3%) and max drawdown (55%) to that of the S&P 500.

Winners, losers, and some caveats

As with all portfolios, power laws are applicable here as well. A few of the winners contributed a major chunk of our portfolio gains. Even though we filtered for a minimum of $1 billion company valuation (as of 2000), firms like Moody’s, Equifax, Hershey, etc. managed to give us a 1,000%+ return.

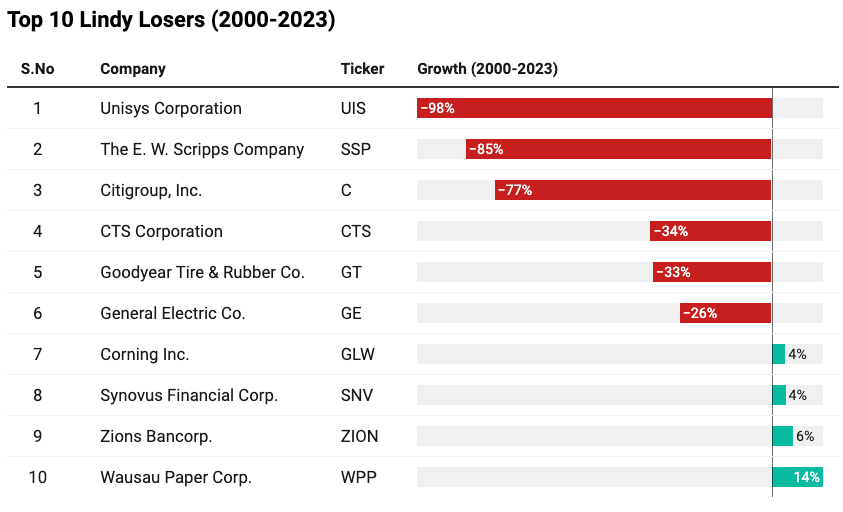

But being a 100-year-old legacy company did not prevent you from wipeouts. GE was the biggest company in the world in 1999, and it has fallen by 25% in the last 20 years! This is the same period during which the S&P 500 was up ~400%! Other famous names include Citigroup, which never regained from the Global Financial Crisis, and Unisys Corporation, which never actually survived the dot-com bubble.

The astute among you might have noticed that we equally split the investments across our Lindy portfolio. If we do a market-cap-weighted portfolio, the results are not so impressive, and the portfolio slightly underperformed the market. This was mainly due to the biggest companies in the list (GE (12.5%), Corning (9%), and Exxon Mobil (7.5%)), all underperforming the market during the past two decades.

There are a few more limitations that you should be aware of before trying to replicate this [Portfolio raw data and holdings are shared at the end of the sheet]

Our portfolio is not rebalanced annually, nor is it updated every year (with the new companies that make it into the 100-year list)

The analysis is prone to survivorship bias — Given that we started with companies that were surviving as of 2017, there might be other 100-year-old companies that died off between 2000 and 2017.

We believe a few, less objective quality checks like the industry tailwind, management competence, etc. could have improved our returns considerably more.

Time is the friend of the wonderful company, the enemy of the mediocre. — Warren Buffett

It is often said that time is the best filter for quality, and the only way a company can survive more than a century is to be a wonderful company. Jeff Bezos was once asked how Amazon became so successful, and his response gives us an insight into what it takes to build companies that last generations.

I very frequently get the question: 'What's going to change in the next 10 years?' And that is a very interesting question; it's a very common one.

I almost never get the question: 'What's not going to change in the next 10 years?

' And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two -- because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that's going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

It's impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, 'Jeff I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher,' [or] 'I love Amazon; I just wish you'd deliver a little more slowly.'

Impossible. And so the effort we put into those things, spinning those things up, we know the energy we put into it today will still be paying off dividends for our customers 10 years from now.

When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

Finally, if you consider that our lives and the world around us are changing fast, we will leave you with this amazing passage by Nassim Taleb.

“Tonight I will be meeting friends in a restaurant (tavernas have existed for at least twenty-five centuries). I will be walking there wearing shoes hardly different from those worn fifty-three hundred years ago by the mummified man discovered in a glacier in the Austrian Alps.

At the restaurant, I will be using silverware, a Mesopotamian technology, which qualifies as a “killer application” given what it allows me to do to the leg of lamb, such as tear it apart while sparing my fingers from burns. I will be drinking wine, a liquid that has been in use for at least six millennia.

The wine will be poured into glasses, an innovation claimed by my Lebanese compatriots to come from their Phoenician ancestors, and if you disagree about the source, we can say that glass objects have been sold by them as trinkets for at least twenty-nine hundred years. After the main course, I will have a somewhat younger technology, artisanal cheese, paying higher prices for those that have not changed in their preparation for several centuries.”

Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. A lot of work goes into these articles, and if you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to access all issues.

If you enjoyed this, you will find this interesting:

Over a rolling 10-year period in the U.S. from 1926 to 2018, value stocks have beaten growth stocks 84% of the time.

- How to identify undervalued companies?

- Does value investing still work?

- How did value-based ETFs perform compared to the market?Data

I’m also writing a post about the Lindy Effect this week and this post is excellent. Well done. I’ll link to this article and quote it in mine.

Thanks. Great post. Especially appreciate that you included the Bezos quotes.