Welcome to the latest Ideastorm. Market Sentiment curates the best ideas and distills them into actionable insights. Join 36,000+ others who receive curated financial research.

Actionable Insights

Even with a clear edge, generating consistent alpha is difficult for investors. While it’s logical that taking a constant and moderate amount of risk is the best bet to win long-term, most investors don’t behave rationally when given the opportunity.

If you have a concentrated stock position, it requires an average annualized alpha of 13% over the index to be worth taking the additional risk of holding it over a diversified index.

Over 13% of regular gamblers won over a two-year period — But less than 1% of day traders reliably generated a positive return two years running.

S&P Global report reveals that active managers' outperformance in the first five years didn't predict success in the subsequent years.

1. Can you win when the odds are in your favor?

The holy grail of investing is finding a consistent edge. Imagine if you could predict with 60% certainty whether the market will go up or down tomorrow — theoretically, this should make you a billionaire in no time. But, in reality, most investors cannot take advantage of this edge.

Don’t believe us? — Consider the coin flip experiment by Victor Haghani, one of the founding partners of the now-infamous hedge fund Long Term Capital Management.

You walk into a room with $25. There is a biased coin on the table, which gives a 60% probability for heads. If you make the correct call, you double your money; otherwise, you lose the bet amount. You can bet any amount of your total portfolio on each bet, toss the coin as many times as you want, and change your bet amount each time. The only catch is that if your balance goes to $0, it’s game over. You have 10 minutes — How much do you think you will make?

Before going forward, we highly recommend you play this simulation and see how much you can make.

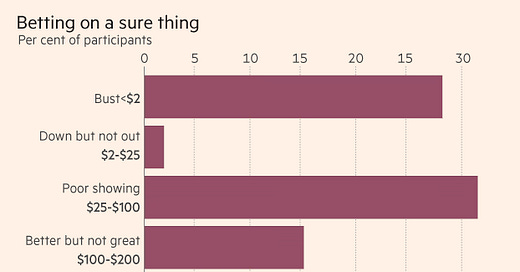

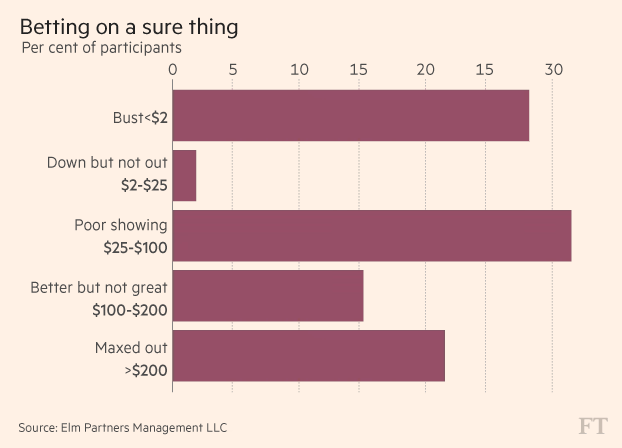

Haghani conducted the experiment on finance students from top colleges and analysts and associates from leading asset management firms. The results were disastrous. Even with a very apparent edge,

28% of the participants went bust

33% had less capital than they started off with

Only 22% of participants had made >$200 (The limit set by the experimenters as the payouts and bets were real $ — The cap of $250 was set as the expected value of the experiment was $3.2M!)

The main problem you would face while playing this simulation is how much to bet. Some of you might bet your total portfolio on one coin toss and bust out, while others might bet too little, which minimizes the total outcome but preserves your portfolio.

The right way to play this game would be to use the Kelly Criterion, which shows that you should only bet ~20% of your portfolio on every toss. If you do this, you have a 95% chance of getting to the maximum payout of $250.

The researchers conclude by raising an important question:

If a high fraction of quantitatively sophisticated, financially trained individuals have so much difficulty in playing a simple game with a biased coin, what should we expect when it comes to the more complex and long-term task of investing one’s savings?

Source: Observed Betting Patterns on a Biased Coin — Victor Haghani, Richard Dewey

2. Does fortune favor the bold?

If you made a very successful investment or are a top executive in a company, chances are you hold most of your wealth in a single stock. What would you think is the best choice for building wealth long-term?

The media is full of stories of investors and employees who held on to stocks like Amazon, Google, and Tesla. But the performance of most stocks is a far cry from these exceptional successes.

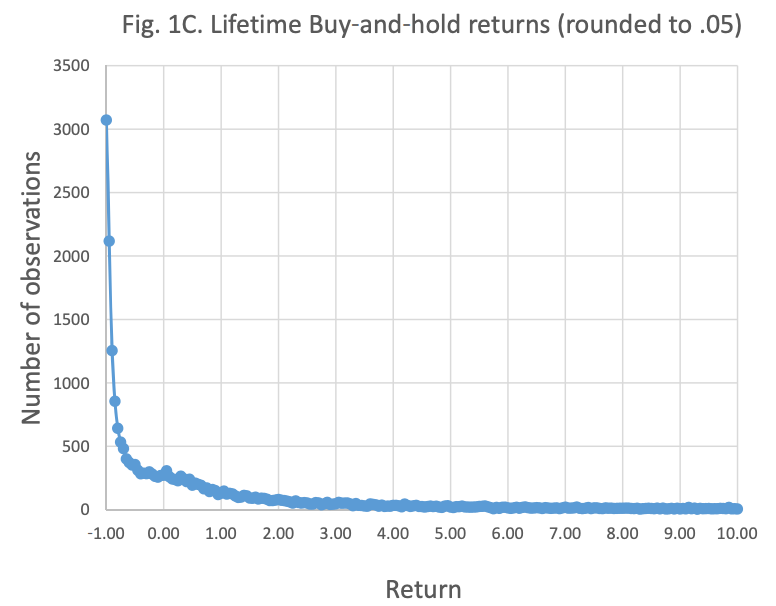

Across the 25,967 stocks listed in the U.S. from 1926 to 2016, the most common one-decade buy-and-hold return was -100%. The conventional wisdom on long-term compounding rarely applies to concentrated stock positions — the risk of capital destruction is too high.

In this paper published in The Journal of Wealth Management, the authors argue that the benefit of liquidating a concentrated position significantly outweighs the tax burden of any such liquidation (even when the stock had a higher average return than that of the index and the capital gain tax was assumed to be at 30%).

This was due to the median performance of individual stocks being so low compared to the index. Once you have a substantial negative return (common in individual stocks — the median annualized volatility of IPO stocks in the first five years after listing was ~50%), it’s hard to compound your way out of the loss.

The stock should have an average annualized alpha of 13% over its corresponding index to make it worth taking the additional risk of holding it over a diversified index.

Source: Perils of Volatility for Wealth Growth and Preservation — Nathan Sosner

3. Day Trading vs Gambling

When a study analyzed the performance of 18,000 regular gamblers in casino games, only 13% won over a two-year period. But, less than 1% of day traders reliably generated a positive return two years running.

On any given day, if you walk into a casino and play a game like blackjack, roulette, or slots, you have a 30% chance of making a profit. The only way to win would be to quit while you are ahead, and most of us won't.

But continuing to gamble is a bad bet.

Just 11% of players ended up in the black over the full period, and most of those pocketed less than $150.

The skew was even more pronounced when it came to heavy gamblers. Of the top 10% of bettors-those placing the largest number of total wagers over the two years-about 95% ended up losing money, some dropping tens of thousands of dollars.

How Often Do Gamblers Really Win? — WSJ

While these numbers look atrocious, they are nothing compared to day trading stats. By gambling, you have a 13x better chance of making a profit than when you are day trading.

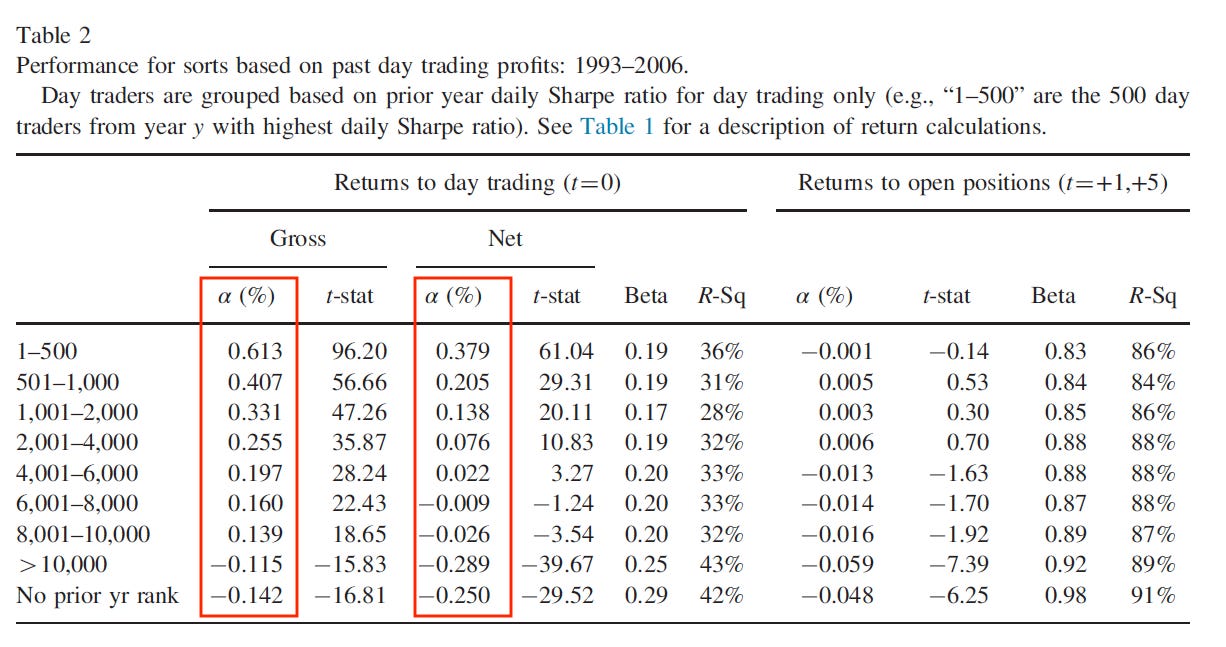

The study evaluated the long-term performance of 450,000+ day traders from 1992-2006 in the Taiwanese stock market. The data contained 3.7 billion transactions with a transaction value of $10 trillion, and almost all the day trading was done by individual investors. In a given year, 20% of day traders earned a profit net of fees. But less than 1% of traders from this group could generate a profit the following year.

The critical question is whether the alpha produced by this 1% of traders results from luck or skill. This is where it gets interesting. Data shows that the most successful investors continue to earn strong returns, highlighting that some traders are indeed skilled.

The top 500 traders (0.1% of the population) had clear performance persistence and earned outsized alpha of 61 bps per day before costs and 38 bps per day after fees.

In aggregate and on average, trading is hazardous to your wealth. Unless you are in the top 0.1% of traders based on skill, you are much better off gambling -- or, better yet, investing in a low-cost, diversified portfolio.

Source: The Cross-Section of Speculator Skill: Evidence from Day Trading — Barber et al.

4. Persistence of active performance

While we have covered the outperformance of passive over active multiple times, a common argument that comes up is most active managers are not all active managers, and “most of the time” is not all of the time.

Thankfully, S&P Global produces a yearly report that tracks the persistence of active management performance. The test is simple — If the outperformance was due to the genuine skill of the manager, it was likely to persist, whereas if the outperformance was due to luck, it would eventually run out.

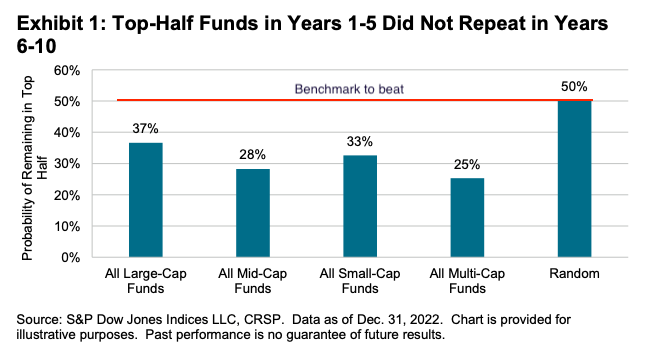

For the analysis, S&P picks the top managers (top 50%) in each fund category for the first five years and checks what percentage of these top managers appeared in the top half of fund performance in the next five years. If the performance were completely random, we would see 50% of winners in the first five years to win in the second five years. If it was due to skill, we would see substantially more than 50% repeated in the second interval.

The results indicate that this was not the case — In none of the fund categories, outperformance in the first five years could predict outperformance in the subsequent years.

Source: U.S. Persistence Scorecard Year-End 2022

If you found this recently, the poll is closed. Here is the deep-dive:

Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. A lot of work goes into these articles, and if you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to access all issues and vote on deep dive polls.

great job