How safe are stocks in the long run?

Evaluating data from 39 developed countries over 150+ years

We are publishing this without a paywall. Please share widely.

By the end of the 1980s, Japan was the place to be for investors. Japan’s stock market was the largest in the world in terms of market capitalization; its manufacturing was the envy of the world, and Japanese tech giants were doing the robot dance way before it was cool. The companies were doing so well that they bought out Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center and Pebble Beach golf resorts in multi-million dollar deals.

At its peak, it was rumored that Tokyo’s Imperial Palace was worth more than all the real estate in California — Yup, a patch of land in Tokyo, in theory, could buy you Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and all the beaches along the Pacific Coast. Makes perfect sense, right?

No one loves a never-ending party, especially central banks. By 1989, property prices were skyrocketing, and the equity market was in an explosive upswing. The Bank of Japan started feeling the heat and decided it was time to bring out the proverbial wet blanket with interest rate hikes. The Nikkei 225, which had reached a dizzying high of nearly 39,000 at the end of 1989, began to tumble.

What investors thought was a minor blip turned out to be a decade-long crash. The Japanese stock market dropped 60% between 1989 and 1992, and the real estate market also suffered a significant downturn — with prices falling by an incredible 70%! Japanese market still hasn’t recovered the heights it achieved during the 1989 rally, and the prolonged economic stagnation is referred to as Japan’s lost decades.

While the chart by itself looks horrifying, the real-life implications are even worse. Consider a Japanese worker who started working in 1980 and investing in the stock market. Assuming the worker invested $1,000 yearly over a 30-year career, by the time he/she retired in 2010, the $30,000 capital would have turned into $20,710 — a -31% return on invested capital over 30 years. In fact, from 2000 to 2010 (the last ten years of their career), there were only two years in which their total portfolio would have been green. Add to this the aging demographics; many older Japanese plan to work forever.

A realized loss over a long period is highly damaging to an investor as it would consume much of their viable saving period without generating wealth. Japan’s experience is not unique, and several developed countries have realized worse performance or even complete stock market failure.

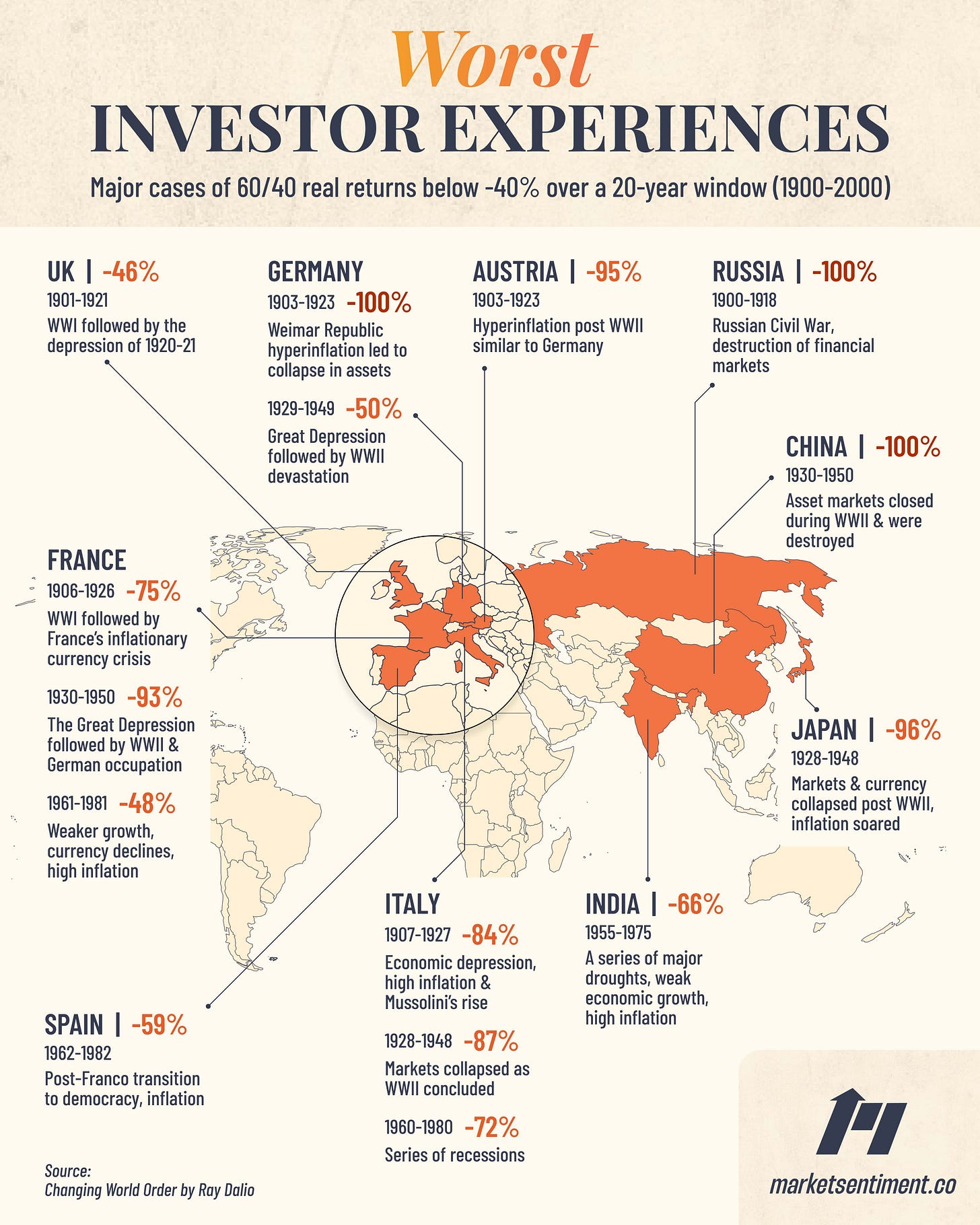

Virtually any one of these countries [highlighted below] was or could have become a great, wealthy empire, and they were all reasonable places for one to invest, especially if one wanted to have a diversified portfolio.

Seven of these 10 countries saw wealth virtually wiped out at least once, and even the countries that didn’t see wealth wiped out had a handful of terrible decades for asset returns that virtually destroyed them financially. — Ray Dalio

The problem with only using the U.S. Data

Consider this thought experiment:

Conventional wisdom indicates that stocks are safe over long holding periods and that young investors should be heavily biased toward stocks. The U.S. stock market has historically rewarded long-term investors:

Over a 15-year period, there was only a 0.2% chance that you would lose money in the U.S. market.

If you expand the study to 1890 and add inflation to the mix, there was only a 1.2% chance of loss in buying power over a 30-year horizon.

But this ignores a lot of biases in the data:

The U.S. return history is relatively short at 120 years — This offers limited statistical information about what happens over 30-year horizons.

Just considering the U.S. market is an easy data and survivorship bias — If you do the same study in another developed country like Germany/France [refer to worst investor experience chart] that went through multiple crises, these results would be very different.

Finally, the U.S. luckily did not have an outlier event, such as the stock market permanently disappearing in Czechoslovakia or hyperinflation in Austria.

A better way to avoid these biases would be to look at how developed markets have performed throughout history.

Evidence from developed markets

Instead of taking just one market, researchers consolidated data from 39 developed countries over a period of 1841 to 20191. By doing this, we can move away from the U.S.-centric design and have a substantially broader view of risk over long horizons.

As expected, on average, the stock market has given excellent returns long term — A $1 investment will grow into $7.38 in 30 years. But, as we can see from the histogram below, there is substantial uncertainty in investment outcomes for long-horizon investors.

The distribution suggests that the −21% real return realization in Japan over the past 30 years is not exceedingly rare. In fact, this observation lies in the 9th percentile of the wealth distribution.

Although this evidence suggests that Japanese investors were unlucky, their experience appears to be a reflection of the substantial risk exposures of long-term equity investors.

If you do the 30-year analysis just using the U.S. data, you will come to the conclusion that there is just a 0.5% chance [probably what you voted in the poll] that the U.S. will experience something similar to what occurred in Japan. But, if you consider other developed markets throughout history, the probability jumps to 9%!

The distribution based solely on U.S. data indicates a low 1.2% probability of a loss in buying power over a 30-year horizon. The full sample distribution reflects a much higher probability of loss at 12.1%.

The abundance of similar examples suggests that the U.S. distribution is overly optimistic with respect to loss probabilities.

Optimal portfolio allocation

To provide a practical application to the above findings, we can create the optimal allocation to stocks for an investor in a developed country. Consider a two-asset portfolio between stocks and an inflation-protected risk-free asset2.

An investor who only considers the U.S. market data will allocate 75% of their portfolio to stocks (30-year investment horizon) compared to the 43% optimal allocation based on developed country data.

Across all the cases, investors relying on the broader developed country dataset tend to be more conservative with the stock allocation.

The concept of surviving on average is irrelevant. You have to survive every day. Which means, really, that you have to survive on the bad days. — Howard Marks

The Japanese market should be a cautionary tale for investors banking on seemingly perpetual market upswings. A myopic view based only on U.S. history ignores the broader historical market behaviors across developed nations.

For someone who has only invested in the U.S. market, it has worked for a long time, and most now believe this is simply how the world works. But, as we just saw, even the most developed markets undergo periods of massive wealth destruction.

To close, we will leave you with Ray Dalio’s thoughts on using history as a guide and how rare it is:

Most investors base their expectations on what they have experienced in their lifetimes, and a few more diligent ones look back in history to see how their decision-making rules would have worked in the 1950s or 1960s.

There are no investors I know and no senior economic policymakers I know—and I know many, and I know the best—who have any excellent understanding of what happened in the past and why.

In looking at the returns of the US and the UK, one is looking at uniquely blessed countries in the uniquely peaceful and productive time that is the best part of the Big Cycle. Not looking at what happened in other countries and in times before yields a distorted perspective.

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order

Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. A lot of work goes into these articles, and if you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to access all issues.

If you enjoyed this, you will find this interesting:

One of the most overlooked aspects of investing is Shannon's Demon: Using it, we can consistently generate positive returns from two uncorrelated assets having zero expected long-term returns. Data, references, and footnotes

Stocks for the long run? Evidence from a Broad Sample of Developed Markets — Anarkulova Et al. (open access)

Interesting read. However, a buy-and-hold 30 years strategy is not per se the typical case (before pension). A more realistic scenario would be to "buy every month for 30 years" and evaluate the CAGR at the end of the period. This will move the expected reward more closely to the mean, as one basically takes 360 samples from the presented distribution (though every next draw has a 1 month shorter duration).

Great article. What makes international diversification so much more difficult, though, other than identifying investment opportunities, are the randomly appearing U.S. sanctions. Many of the BRICS+ countries and are either off-limits for U.S. investors, have in recent years become off-limits (such as China Mobile and Russian companies), or are in danger of becoming off-limits soon (Hong Kong is rumored to be sanctioned, which would affect the stock market for most foreign investors in China). India, for now, is still okay, but for how much longer? Even NATO countries, like Turkey, are not safe. I am not trying to dissuade anyone from investing in those countries where U.S. investors are still allowed to invest, but one needs to have a Plan B. Michael Burry, who made a fortune predicting the 2007 subprime crisis, recently significantly increased his Chinese investments, but he also bought puts. He didn't say it, but I suspect it was as a hedge against randomly appearing U.S. sanctions.