Great Expectations

You might not make the returns your parents made

The most important part of every plan is planning on your plan not going according to plan — Morgan Housel

In theory, counting cards is simple. By tracking which cards have already been dealt on the table in a game of Blackjack, you can calculate the odds of a particular card being drawn by the dealer. In his book Bringing Down the House, Ben Mezrich discusses the MIT Blackjack team that used this edge to win millions of dollars in Las Vegas. While it might look like gambling to outsiders, successful card counters have one of the best money management systems.

The trick is that the card counters know they are playing a game of odds, not certainties. Even if you have a 10% edge over the house, you can be wrong 40% of the time. So, on a given hand, you can never be sure about the outcome and bet your entire bankroll. To make the game work in their favor, card counters keep a large margin for error. They rarely bet more than 1/100th of their bankroll on a single hand1. This way, they make sure that they have enough money to withstand the inevitable string of bad luck.

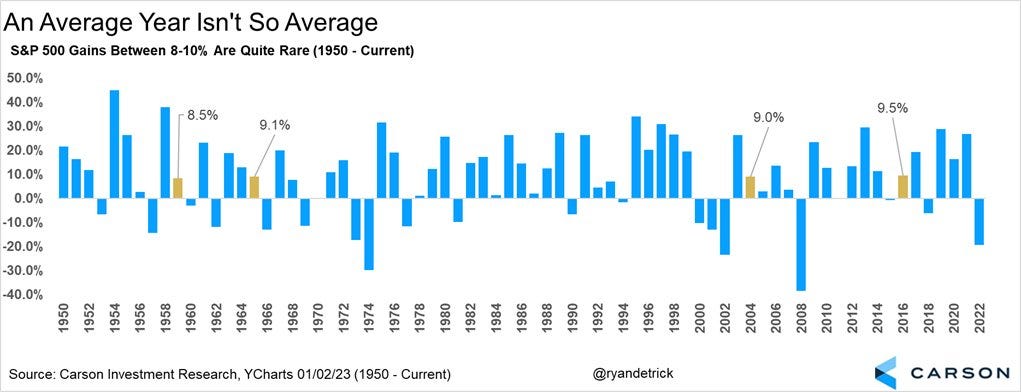

U.S. Economist John Kenneth once famously said that The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable. The economic output is affected by the aggregate activity of billions of people and thousands of seen and unseen forces. The same applies to the stock market — Even though the average return of the S&P 500 over the past eight decades was 9%, it rarely produces that in a given year.

This brings us to the key issue facing long-term investors and retirement planning — If you believe in mean reversion, the golden age of investing is almost certainly over, and you will not enjoy anything like the returns your parents made.

To give you an idea of how much the recent few decades have biased our view, consider this (real returns):

Performance of stocks:

Annualized return of global equities from 1981 to 2021 — 7.4%

Annualized return of global equities from 1900 to 1980 — 4.3%

Performance of bonds:

Annualized return of global bonds from 1981 to 2021 — 6.3%

Annualized return of global bonds from 1900 to 1980 — 0%

Warning signs

The ubiquitous disclaimer that past performance is no guarantee of future returns has rarely been more apt. In the U.S.,

Stocks are expensive, and the equity premium is now at its lowest in decades.

Simply put, the equity risk premium measures how much extra return you will get investing in a risky asset compared to a risk-free asset like treasury bills. The rationale is that investors are risk-averse, and they need a higher return to justify investing in a risky asset like stocks.

Right now, the equity risk premium for the S&P 500 has fallen to its lowest levels in decades. The last time it was this low was before the Global Financial Crisis.

AQR research recently published a report in which they argued that the U.S. outperformance in the past few decades was mainly driven by valuation changes rather than fundamental improvements in the economy [emphasis ours]

Since 1990, the vast majority of the US’s outperformance versus the MSCI EAFE Index (currency hedged) of a whopping +4.6% per year, was due to changes in valuations.

The culprit: In 1990, US equity valuations (using Shiller CAPE) were about half that of EAFE; at the end of 2022, they were 1.5 times EAFE. Once you control for this tripling of relative valuations, the 4.6% return advantage falls to a statistically insignificant 1.2%.

In other words, the US victory over EAFE for the last three decades—for most investors’ entire professional careers—came overwhelmingly from the US market simply getting more expensive than EAFE.

As value investing teaches us, winning simply because the other person is willing to pay more is not a sustainable strategy.

A perfect tail-wind from Bonds:

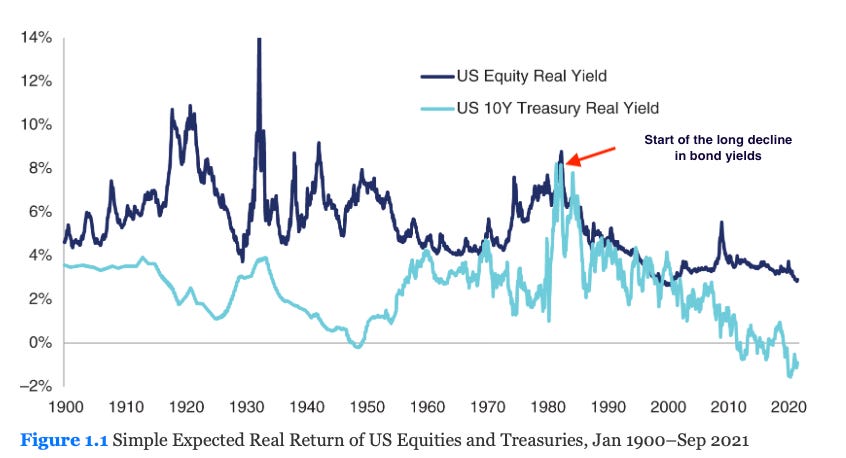

To value any asset class, we calculate the present value of future cash flows, with the common element being the risk-free rate. The steady decline of bond yields started in the 1980s — When interest rates fell, older bonds that were issued at higher interest rates became more valuable since they had higher coupons compared to the new bonds. This decline provided bondholders with fantastic capital gains.

Even with the recent spike in yield to 5%, we are nowhere near the 16% nominal rates the U.S. had in the 80s. The rising valuation for stocks and the tailwind from reducing bond yields meant that a classic retirement portfolio like the 60/40 had incredible returns over the past four decades.

Extrapolating this strong market performance into the future might not be the smartest bet, and acknowledging current market conditions has significant implications for investors. There are a few ways in which we can handle the lower expected returns:

Retirement savers must save more as the market offers less

Allocate a larger proportion of your portfolio to equities

Add illiquid/private assets

Factor-based investing for higher risk-adjusted return

It's crucial to recognize that each of these strategies, while offering its unique advantages, also carries inherent limitations. Let’s dig in: