Getting Risk Right

The Gap Between Perception and Reality

In our last article, “How much risk can you handle?" we started off by asking you what you thought about your risk profile.

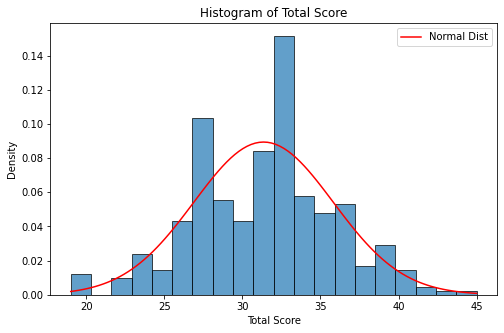

45% of you voted that you have an aggressive investing approach, compared to only 13% who voted they are conservative investors.

But how did you actually score on the quiz?

Only 16% of the 320 responses submitted could be classified as aggressive investors. Eighty percent of the respondents were moderate investors, and only four percent were conservative investors.

The skew towards aggressive can be explained by the fact that an investor who reads Market Sentiment is much more financially savvy than the average investor, and savvy investors tend to understand and take more risks in the market1.

Similar to the findings from Morningstar2, our results also follow a normal distribution.

The discrepancy — where nearly half the respondents believe they are aggressive investors, but only 16% actually score as such reveals an interesting insight.

The Gap Between Perception and Reality

Investors often misjudge their own risk tolerance. Investors tend to overestimate their ability to handle risk during bull markets. Here’s how most of us think about risk3:

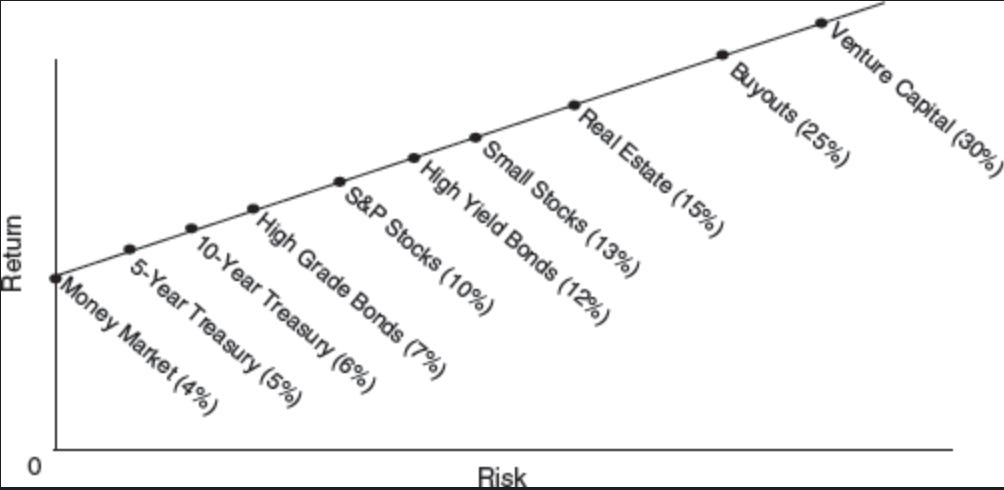

Consider two cases where you invest in treasury notes vs. investing in an upcoming small-cap stock. With treasury notes, you are assured a return of 3 to 4% at the end of the year. There is only one highly unlikely scenario of a U.S. default where you would end up not getting a payout.

Compare this to the small-cap, where the range of outcomes is much higher. The company can go out of business, where you have to mark your investment as a total loss, or the company can double its stock price in a year, giving you a windfall.

To compensate for this extra uncertainty, you expect a higher return (when compared to the treasury notes). No one would invest in small-caps if their average expected return were comparable to treasury bonds.

If we extrapolate this logic to all other investments, we get a familiar chart like this:

The problem with the above approach is that investors often draw the wrong conclusion after seeing it. It only communicates the positive relationship between risk and return. In good times, it’s easy to see the high returns of riskier investments and think that one should have invested in them.

The correct way to think about it is that in order to attract capital, riskier investments have to offer the prospect of a higher return—not a guarantee of a higher return. If we add this nuance to the above risk-return chart, we can visualize the risk-return relationship much better.

Optimal Equity Allocation by Risk Tolerance

Even if you consider yourself an aggressive investor, what’s the optimal amount you should allocate to equities? — The optimal equity allocation is not just a factor of risk tolerance: it’s also based on your country, investment time horizon, and expected returns.

Let’s dig in: