Welcome to the 300+ investing enthusiasts who have joined us since last Sunday. Join 29,812 smart investors and traders by subscribing here. It’s totally free :)

Check out our - Best Articles | Twitter | Reddit | Discord

The search by the elite for superior investment advice has caused (funds), in aggregate, to waste more than $100 billion over the past decade. - Mystery guy

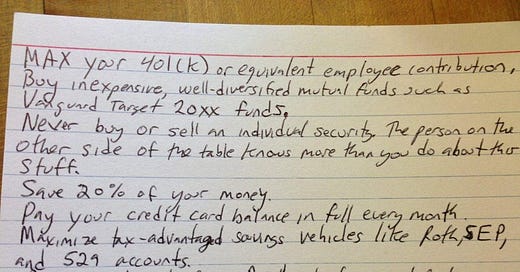

In 2013, a social science professor by the name of Harold Pollack said something audacious during an interview: “the best financial advice can fit on a 3 by 5 index card and is available for free in the library.” When viewers wrote in asking for the index card, he quickly scribbled together a set of 9 rules that went viral.

While this is definitely not a shortcut to getting rich, the point “Pay attention to fees - Avoid actively managed funds”, got me thinking.

Financial advice, like any business, needs repeat customers. A lot of financial advice - especially the business of giving stock tips - is like sugar. Its goal might not be to keep you healthy, but rather to keep you coming back for more. The advice might not be harmful but there might be much simpler things you can do that nobody talks about. As my friend Kris Abdelmessih said:

“Nobody has the incentive to tell you the truth. Big Food or Big Ag will never commission a study on “intermittent fasting”. No single entity profits from the absence of eating 3 American-sized meals a day.”

The most obvious such problem that’s often overlooked is the importance of the fees. Let’s see how it can impact your returns in the long run.

How hedge funds make money

A number of smart people are involved in running hedge funds. But to a great extent their efforts are self-neutralizing, and their IQ will not overcome the costs they impose on investors.

- Mystery guy

The “zero management fee” model is what all funds would use in a perfect world. Such partnerships charge a performance fee only when the fund manages to turn a profit on the money invested. In some cases, there would even be a “hurdle” - a minimum threshold that the profits would have to cross for the manager to be paid. But in reality, a very small number of fund managers use this model.

The “Two and Twenty” fee structure is the most common form of compensation for most hedge funds. It charges a management fee of 2% on the total Assets under Management, and a 20% performance fee on any profits accrued. The idea is that a larger performance fee aligns the interests of managers with investors while the management fee gives them some immunity against market volatility.

Managers get paid even during periods of underperformance while investors pay them with the very savings that they want to protect. But the worse part is how the leakage in fees adds up over time…

The tyranny of fees

As Gordon Gekko might have put it: “Fees never sleep.”

- Mystery guy

What if I told you that the fees you pay to your broker over a lifetime could equal the gains in investment? Well, that isn’t the case actually - in reality, the fees are much greater than the gains!

In his fantastic article “Bequeathing your assets to your Broker”, William Bernstein runs a simple simulation: At the age of 25, you give a fund manager $100,000 to manage, and he turns over a long-term return of about 8%. But fees will reduce your return while adding to the manager’s portfolio which compounds without any fees. Assuming a 1.5% management fee1 and 20% performance fee, this is how the portfolio values of you and your manager would look:

You will have up and down years, but your manager has a steady stream of income because of your assets... and by the time you retire at 65, you will have $764,000. Not bad - but the manager will have more than $1.24M (at zero initial investment!) In reality, your returns will be further cut down by frequent turnovers in your portfolio and capital gains taxes. The outcomes don’t even depend on the actual performance of the hedge fund: Nick Maggiuli’s analysis shows that on average, it takes about 17 years on average for the fund to beat the investor. The higher the management fee of your fund, the lesser you end up with at retirement:

Now, let’s look at what happens with a low-cost ETF: If you invest in an ETF with just a 6% annual return (2% lesser than the active fund), you will have $933k at the end of 40 years while the ETF makes just $3,017.2 That's about $280k more than what you would get with a 2 and 20 fund - but that extra money can last for more than 10 years of retirement, as the figure below shows:

Even the unluckiest 2 and 20 hedge fund would overtake its investor in 23 years. On the other hand, a low-cost ETF would take more than 1500 years to do the same thing! What do ETFs do differently? And what impact have they had on the industry?

The impact of ETFs

If a statue is ever erected to honor the person who has done the most for American investors, the handsdown choice should be Jack Bogle.

- Mystery guy

Though the Efficient Market Hypothesis started gaining traction in the 1960s, there was no cost-effective way to track the market for most investors. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the first Index Fund was launched and John Bogle began advocating for low-cost index funds and ETFs as the best option for individual investors.

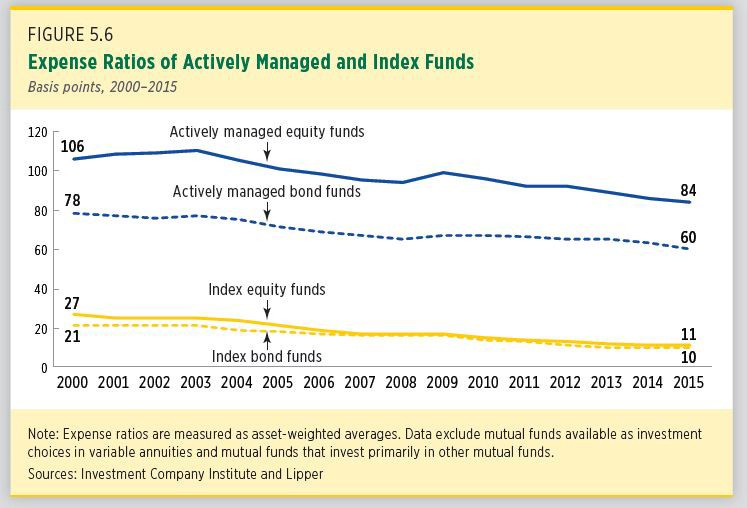

ETFs have an extremely low expense ratio (around 0.1%) and they don’t pass on the transactional costs of rebalancing the index to their customers. Though they pass up on the management fees, ETFs have the advantage of volumes and price momentum as more and more investors choose them over actively managed funds. The difference in expense ratios is enormous:

ETFs are currently responsible for about 37% of the notional trading volume in the market, up from less than 5% in 2000. ETFs have also led to the decline of active management fees, and the inception of zero management fee funds by large firms like Fidelity.

One concern is that passive investing will decline in performance once it occupies a larger portion of the market. John Bogle was concerned about “chaos” once the proportion reaches 90% - but this scenario is a long way off!

The bottom line: When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Streeters charging high fees, it will usually be the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients. Both large and small investors should stick with low-cost index funds.

- Mystery guy

So what’s with all the quotes strewn throughout this article? All of them are from the 2016 annual letter to shareholders written by the mystery guy… Mr. Warren Buffett. In this letter, Buffett tells the story of the $500,000 open bet he made: “No manager can choose a set of at least five actively managed funds that would beat the Vanguard S&P500 index fund after fees, over one decade.” Ted Seides was the only person who answered the call, and he selected five funds-of-funds.

Despite a neutral market environment and the huge financial incentive to do well, the five funds averaged 2.2% in returns against the index fund’s 7.1%. And this was even before fees were considered - 60% of all gains were diverted to the two levels of fund managers! Buffett ended by saying that there are definitely competent managers out there who justify their fees, but the problem is in finding them among the thousands of registered professionals.

So if you’re invested in index funds, good for you. If not, maybe it’s time to calculate the impact of management fees on your returns - Don’t leave that footnote unexamined.

Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription.

Interesting finds: I’ve been binging on David Senra’s Founders podcast over the last week - He reads biographies and autobiographies of great entrepreneurs, investors, and doers that could take you days to read and compresses their insights into an hour or two! I love the insights from the podcast and highly recommend his episode on Charlie Munger’s autobiography to start with.

Footnotes

As management fees have dropped from 2% to about 1.4 to 1.5% on average.

People who invest in hedge funds aren’t naive - Hedge funds have other advantages, like minimizing drawdowns and hedging against market crashes by sacrificing returns. But if you’re a purely long-term investor, is the compromise worth it? (Also, hedge funds might not be working all that well.)

If you enjoyed this piece, please do me the huge favor of simply liking and sharing it with one other person who you think would enjoy this article! Thank you.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Please do your own research before investing.

Nice article as usual! This newsletter is consistently one of my favorite weekly reads. As a fiduciary RIA and financial planner myself, one of toughest parts about this conversation I've noticed amongst financial writers and publications is the lack of distinction/nuance in the discussion of total cost. Financial advisors tend to get lumped in (frequently) with actively managed funds, hedge funds, and other "Wall St" entities (whatever that means), as some sort of boogieman profit leaches. Thankfully, this newsletter does a great job of both definitional explanation and thoughtful commentary. Of course, working with a fiduciary advisor comes at a cost, a significant one indeed over a lifetime. So, the numbers and charts laid out in the article remain true and should be heavily considered. The funny part is, more than 16 years of boots-on-the-ground experience has given me one, distinct thesis: Most people who would actively consume content like this are fundamentally interested/curious about personal finance in general, and would almost never consider hiring a financing advisor - The cost-benefit ratio just doesn't make sense. IMO, good fiduciary advisors and firms focus their efforts on developing a clientele who are either not interested in personal finance or simply too busy to give a financial life plan the urgency of thought it requires. Both of these distinct groups typically understand the importance of financial planning, but lack the natural curiosity or the bandwidth of time in their life to squabble over cost. I realize to the readers of this newsletter, that's an utterly ridiculous statement to read - After all, how much time does it really take to max out your 401k plan and other tax-advantaged accounts and buy some index funds or ETFs? I agree, but I, along with the collective readers of this newsletter, I am a nerd (and consider that a badge of honor)! So, while I would encourage you and other financial writers to continue writing about this topic, I think increased nuance and context in the conversation about the different layers and types of fees we are all exposed to would be helpful. More importantly than that, for people who are naturally inclined toward personal finance, newsletters like this, and enjoy the process of evermore financial efficiency... I plead with you to not brow-beat your family, friends, and colleagues who choose to work with an advisor. Yes, it's obnoxiously expensive over a lifetime, but consider the opportunity cost. Many people will never have a chance at financial independence without the intervention, accountability, support, and coaching of a financial advisor. DIY investing and financial planning is hard, really hard. So, kudos to all the readers of newsletters like this fighting the good fight, pocketing those management/advisory fees for themselves AND to the folks who have the humility to admit the need some help and raise their hands to ask.

i think it would also be interesting to review how cheap many etfs could be if the asset manager did not cream off a slice of the stock lending ...without this, i wonder how profitable etfs would be and much shallower the markets might be...anything to lessen the casino at work now!