Family

How family owned businesses outperform

Answering to no one is the ultimate situation — Mike Bloomberg on why he did not take his company public

Contrary to popular belief, Mike Bloomberg did not always work for his own company. He started his career at Salomon Brothers in 1966 for a measly $9000/year, and was literally sitting in his underwear counting bonds and stock certificates inside the vaults. He was extremely driven and worked 12-hour days, 6 days a week, for 15 years straight to make partner. Finally, when Salomon Brothers was acquired by another firm, he was unceremoniously let go (though with a cool $10M severance check).

Bouncing back from the setback, he founded Bloomberg in 1981 and the rest is history. It’s currently one of the largest financial institutions in the world generating an annual revenue of more than $10 billion. One of the keys to Bloomberg’s success was his refusal to give up control of his company — Unlike many entrepreneurs who go public once the company has achieved some level of success, Bloomberg kept the company privately owned giving him complete control over its direction and strategy.

Bloomberg believed that taking the company public would distract them from their core mission and could lead to short-term thinking and pressure to meet quarterly earnings targets. Time and again we have seen management of public companies (Tesla, GE, Boeing, just to name a few) make short-term decisions to appease investors and meet analyst expectations which lead to long-term repercussions. By keeping Bloomberg private, and having a whopping 88% ownership of the company, Mike was able to think long-term, take tough decisions, and rise to the top of the extremely competitive Wall Street.

The Principal-Agent Problem

One of the most common issues faced by companies is the principal-agent problem. Let’s say you (the principal) own a company but don’t have the time/energy/expertise to run it. So you hire a CEO (an agent) to run it for you. The principal-agent problem emerges whenever there’s a conflict of interest between the principal and agent.

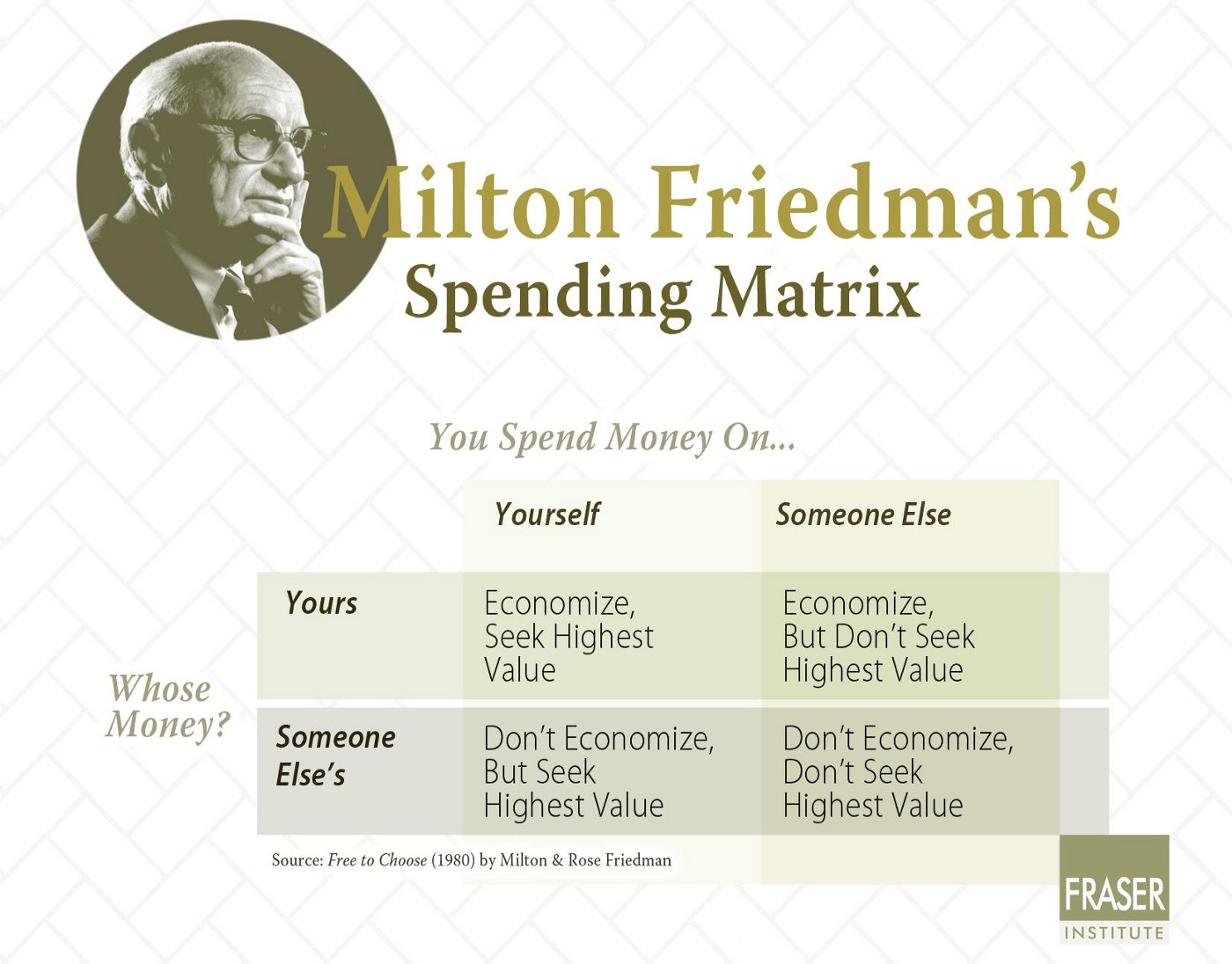

If the CEO you hired is incentivized by the revenue growth of the company, then he/she will do whatever it takes to grow the revenue of the company — Maybe even at the expense of the goodwill your company has created over decades or by taking risky bets since his salary is only based on the revenue growth. The same logic runs over to the cost side as well — Most people are more frugal with their own money than someone else’s.

The issue is also rampant in the investment space where if the financial advisor you hire is paid in commissions, he has more incentive to maximize his fees than your returns.

While there are certain ways to reduce the principal-agent problem, the best solution is to avoid it altogether — This is what family-run businesses excel in. If the company is run by people who have a significant stake in the company, they would prioritize long-term performance over short-term wins.

So, if you want to invest your hard-earned money, why wouldn’t you invest it with owners who are running the company and are in the same boat as you?

What we can learn from family businesses

While everything we discussed can come under conventional wisdom, researchers at Harvard and École Polytechnique did a rigorous analysis of 149 publicly traded, family-controlled businesses with revenues of more than $1 billion — and the results were surprising.

The simple conclusion we reached is that family businesses focus on resilience more than performance. They forgo the excess returns available during good times in order to increase their odds of survival during bad times. A CEO of a family-controlled firm may have financial incentives similar to those of chief executives of nonfamily firms, but the familial obligation he or she feels will lead to very different strategic choices.

Executives of family businesses often invest with a 10- or 20-year horizon, concentrating on what they can do now to benefit the next generation. They also tend to manage their downside more than their upside, in contrast with most CEOs, who try to make their mark through outperformance. — HBR

The researchers found some key traits that differentiate family businesses from non-family businesses, allowing them to survive through tough times better. The family-owned companies

were frugal — Family firms are imbued with the sense that the company’s money is the family’s money and they do a much better job of keeping their expenses under control.

had a high bar for capital expenditure — Corporate executives who are not owners are rarely judicious when it comes to capex. The study showed that family-owned businesses are much more stringent when it comes to new investments

carried little debt — on average, family-owned businesses had only 37% of their capital accounted by debt compared to 47% for nonfamily firms. This allowed them to fare much better during recessions.

acquired fewer companies — this comes from (1) and (2). High-risk high-reward acquisitions were the go-to strategy for corporate executives but family businesses rarely made these deals. On average, family businesses only made half the number of acquisitions as nonfamily businesses.

retained talent better — This was the most surprising insight for us. Even though family-run firms were not paymasters, they managed to retain employees better. The firms focused on creating commitment and purpose, avoided layoffs during downturns, and promoted from within — all leading to better employee satisfaction and retention.

To fully grasp the extent of long-term thinking, listen to the strategy of one executive of a family-run global consumer products company.

We accepted that we’d lose money in the U.S. for 20 years, but without this persistence we would not be the global leader today

Does the market reward family-run businesses?

Now that we understand how family-run businesses are fundamentally different in thinking, let’s take a look at how they have performed in the market. After all, you can still keep majority ownership in your company even if it’s listed publicly.

Credit Suisse used to put together a list of 1000 major family-owned businesses across the Americas, Europe, and Asia Pacific. For inclusion in the list, the company should be publically listed and the founder or their family should have at least 20% of the ownership or voting rights. They evaluated the share price performance of these companies and the results were stunning.

We find our global Family 1000 universe has generated an annual sector-adjusted excess return of 300 basis points since 2006, consistent across all regions - Credit Suisse Research

Let’s dig into which companies these were, how they outperformed, and what we can learn from them:

(Annual subscriptions are now at a 20% discount. E-mail us if you are interested in a group/corporate subscription)