All In

Should your portfolio be 100% stocks?

The concept of surviving on average is irrelevant. You have to survive every day. Which means, really, that you have to survive on the bad days. — Howard Marks

Harry Max Markowitz is an American economist who won the Nobel Prize in economics and also the John von Neumann Theory Prize. His findings were instrumental in the development of the Capital Asset Pricing Model and also in portfolio optimization. Yet, his response was unexpected when asked how he managed his retirement account. (emphasis by author)

I should have computed the historical co-variances of the asset classes and drawn an efficient frontier. Instead, I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn’t in it — or if it went way down and I was completely in it.

My intention was to minimize my future regret.

So I split my contributions 50/50 between bonds and equities.

As Jason Zweig so eloquently put it, there may be nothing across the entire spectrum of human endeavor that makes so many smart people feel so stupid as investing does.

In investing, we rarely choose the optimal solution. Don’t believe us?

Here is a really fascinating thought experiment. Take your time, think through it, and then choose. (Your choice becomes vital at the end)

The “right” answer here is getting the coin toss — Because your expected value is $500K by taking the toss. But realistically, even $100K is a life-changing sum for most of us, and we would take that over a 50/50 chance of getting the million.

The way you voted also gives you an insight into your risk tolerance. The higher the guaranteed payout you require to replace the coin toss, the higher your risk tolerance. Someone who will not take the $400K payout but will take his/her chances with the coin toss will have a comparably higher risk tolerance when compared to someone who will take the $100K payout1.

A recurring question

One of the most common questions we receive is – Why shouldn’t we just put all our investments into an index fund and then call it a day?

After all, a recent study from Vanguard has shown that over the past ~100 years, stocks have outperformed bonds consistently, and any extra allocation to bonds will reduce your overall returns.

While it’s unarguable that over the long term, equity investments tend to outperform, there are some pitfalls that come with a 100% stock portfolio.

Let’s dig in:

1. We always underestimate the downside

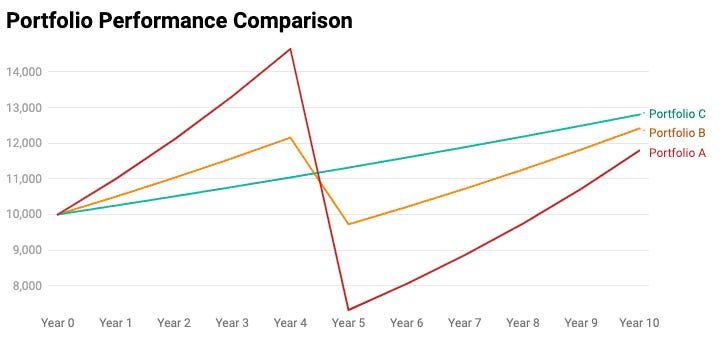

Let’s assume that you are planning to make a long-term investment (10 years) and you have three options.

Portfolio A grows 10% every year consistently but the catch is that once every ten years, it goes through a 50% drawdown. Portfolio B works exactly the same but only returns 5% and has a relatively lower drawdown of 20%. Finally, you have the option of parking your funds in a 10-year term deposit offering 2.5% APY.

The trick here is that most of us tend to allocate more importance to the returns generated by our investments than to their possible downsides. Simple math shows us that a loss of 10 percent necessitates an 11 percent gain to recover. Increase that loss to 25 percent and it takes a 33 percent gain to get back to break even. A 50 percent loss requires a 100 percent gain to get back to where the investment value started. This is why conserving your portfolio is more important than trying for maximum returns.

Coming back to our experiment, portfolio A starts off the strongest generating a yearly 10% return. Portfolio B also outperforms C with a 5% CAGR compared to the pitiful 2.5% return offered by the Term Deposit. But where it gets interesting is once you factor in the drawdown.