A pin lies in wait for every bubble.

And when the two eventually meet, a new wave of investors learns some very old lessons: First, many in Wall Street will sell investors anything they will buy. Second, speculation is most dangerous when it looks easiest. — Warren Buffett

Let’s start with a simple challenge: You have to identify company X from the following clues.

At its peak in March 2000, company X briefly became the most valuable company in the world with a market cap of half a trillion dollars. It was a new era: X provided an indispensable service to all dot-com companies and traded at a P/E ratio of 200+ in 2000. Investors were 100% sure that X will be the one that was going to change everything.

After all, they were selling shovels during a gold rush!

We will get to the answer in a bit. If you were an informed investor during ‘99, you could have avoided a lot of pain. In one of his interviews given to the press, Warren Buffett warned investors about the excess in the stock market. He compared internet companies to the auto industry where even though the latter industry transformed the world, hundreds of car makers became road kill.

Coming back to our quiz, company X is Cisco. Cisco had pioneered the development of networking equipment. Investors poured money into the company betting that the demand for networking equipment would grow exponentially with the internet. Economist Burton Malkiel was one of the few people who pointed out the irony in the situation: At Cisco’s implied growth rate, it would become larger than the entire U.S. economy within 20 years.

Just two years later, Cisco’s stock price crashed by 80%, and 20 years later, it is still ~40% below the peak it touched during the dot-com bubble. Cisco earned ~$12 billion in profits in 2022 and has improved its income by 7x over the last 2 decades. But for the investors who bought in at a PE of 200 in 2000, it’s still a long way to go before breaking even.

What Scott McNealy, CEO of Sun Microsystems1 told Bloomberg just after the dot-com collapse in 2002 became one of the most eye-opening statements on how detached investors become from reality amidst bubbles.

“2 years ago we were selling at 10 times revenues when we were at $64.

At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends.

That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. That assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal. And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10 years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate.

Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes.

What were you thinking?”

It’s impossible not to draw parallels from the dot-com bubble to what’s occurring in the market now.

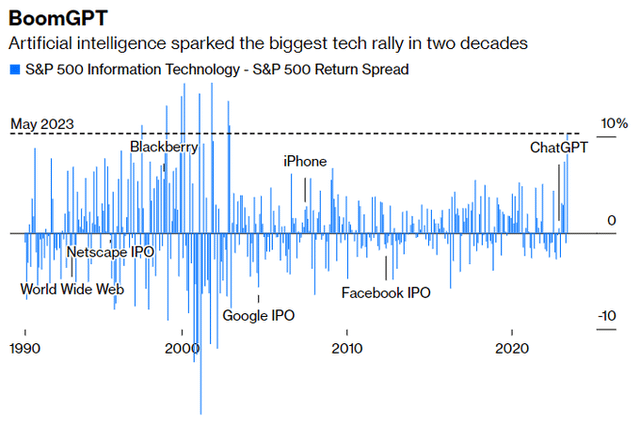

The catalyst for the current rally was the launch of ChatGPT back in Nov’22. It spread like wildfire and reached 100 million active users in just under 2 months — something TikTok took 9 months and Instagram took 2.5 years to achieve. The market impact was also instantaneous: every other tech company started name-dropping “AI” on their earnings calls. VCs and investors have been throwing money at AI giving absurd valuations to AI companies.

How absurd?

NVIDIA NVDA 0.00%↑ is now trading at 37 times its revenue (P/S) and 202 times its earnings (P/E). Read that again — this is not any small-cap upstart. It’s the 4th largest company in the S&P 500 generating more than $5 billion in earnings and is now trading at 200 times its earnings. For context, the stock price must stay the same and then the company has to 6x its earnings just for it to trade at the same P/E as Apple.

And it’s not just NVIDIA. In the last 6 months, Meta is up 112%, Apple 45%, Amazon 43%, and Microsoft 35%. In fact, the last time tech companies beat the rest of the S&P 500 by this margin was during the dot-com bubble.

From the Dutch Tulip Mania in the 1630s to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, if we know one thing about bubbles, it’s how they will inevitably end: with a small handful of winners and a lot of ruin for everyone else.

The problem with bubbles

See if you can identify the recurring theme across some of the biggest bubbles in history

1720 South Sea bubble — The South Sea Company had a monopoly on trade between South America, Mexico & the U.K.

1840s Railway Mania — The first commercial railway in the U.K. sparked intense interest in the new “disruptive technology” of railways.

1990s Dot-Com bubble — Investors believed (rightly in hindsight) that the internet had created a “new economy”

2000s housing crisis — Housing prices soared and home flipping became the new big thing. After all, it’s impossible for housing prices to drop right?

What makes bubbles so hard to resist is that there is always some truth behind the hype. Every transformative innovation is followed by a surge of new businesses trying it out and then mass extinction with only a few of them making it to the other side.

Even if you make the correct bet on the industry, picking winners is hard.

Buffett tried to teach this to us way back in ‘99.

There are three things that might allow investors to realize significant profits in the market going forward. The first was that interest rates might fall, and the second was that corporate profits as a percent of GDP might rise dramatically.

I get to the third point now: Perhaps you are an optimist who believes that though investors as a whole may slog along, you yourself will be a winner. That thought might be particularly seductive in these early days of the information revolution (which I wholeheartedly believe in). Just pick the obvious winners, your broker will tell you, and ride the wave.

Well, I thought it would be instructive to go back and look at a couple of industries that transformed this country much earlier in this century: automobiles and aviation. Take automobiles first: